Optimism is of the essence on the financial markets as 2021 gets underway. Investors are anticipating an economic recovery with a rebound in company earnings, all the while expecting the central banks to continue their generosity and interest rates to remain very low.

Such a combination would provide a favourable context for equity prices to keep on rising. But these factors also indicate the main risks facing the equity markets:

- the economic recovery is not on track or at least disappoints;

- the central banks change course and start to tighten their monetary policy;

- the central banks remain generous but bond yields rise.

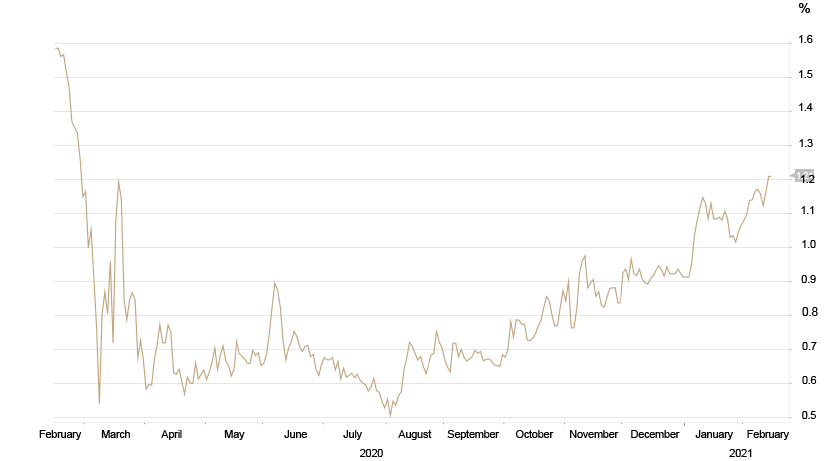

Of these risks, the second seems fairly unlikely to me but the other two cannot be ruled out. The complete reopening of economies still seems very remote at present. And even in the event of reopening, there is no guarantee that the scenario of economic agents rushing to spend everything they were unable to spend in 2020 will materialise. In other words, the recovery could indeed disappoint. As for the possibility of seeing bond yields rise despite the continuation of very expansionary monetary policies, this is exactly what has been happening in recent weeks. In the United States, for example, the 10-year Treasury yield has risen from 0.9% to 1.2% since the start of the year. This reflects expectations of an economic recovery, but also of a potentially more inflationary environment in the medium and longer term. So far, the rise in bond yields has been too small to worry the equity markets, but if it were to continue, the situation could change.

U.S. 10-year bond yield

Source: Bloomberg

2020 showed the futility of the traditional exercise of new year predictions. The possibility of a pandemic plunging the global economy into recession and causing equity prices to fall by some 40% was not on the forecasters’ radar at the beginning of 2020. Nor, in March, did they anticipate that most equity market indices would end the year in positive territory.

Rather than focusing on the short-term outlook for the markets, to my mind it is more relevant to talk about the general framework, the big picture, and the potential implications of this framework on investment decisions.

The experience of the last few years has shown that in the major industrialised countries it has become impossible to create the nominal growth necessary for the system to function properly. In most of these countries, the debt-to-GDP ratio is now historically high, even without taking into account unfunded pension liabilities. The best way out of this impasse would be through a sharp rise in the denominator, GDP, as happened after the Second World War. However, at that time, populations were young and the needs for reconstruction were great. Today, the situation is quite different. Since the financial crisis, the central banks have been trying to stimulate nominal growth mainly by insisting on the inflation component (nominal growth equals real growth + inflation). To do this, they have been pursuing very expansionary monetary policies for years, notably reducing interest rates to zero. Rather than stimulating economic activity, however, their policies have had the opposite effect and have contributed to a structural slowdown in growth. At the same time, the problem of over-indebtedness has only become worse. This problem of over-indebtedness increases both the risk and the danger of deflation and the monetary authorities have therefore become all the more desperate in their efforts to create inflation.

But the pandemic has somehow changed the situation. After the financial crisis, the burden of stimulating the economy fell solely on monetary policy. Today, fiscal policy is seen as the way forward. Fiscal austerity is gradually being phased out and all countries are considering major stimulus packages. (In this respect, it is worth noting that the measures taken by the authorities in 2020 cannot be considered as real stimulus measures. The purpose of these measures was to compensate for the loss of activity suffered by the private sector.) The hike in public spending is expected to be financed by the central banks. The role of the state in the economy will increase and the market economy will continue to be pushed out in favour of a planned economy.

How will this affect investors? First of all, they should avoid having too many preconceived ideas. In recent years, we have seen how quickly rules can change – and the authorities’ influence on the financial markets is increasingly evident. Hence the need to keep an open mind and adapt to events. Nevertheless, there are some discernible trends.

First, although the central banks are officially independent, it is clear that we will rely on monetary policy to maintain an environment in which budget deficits can be financed without disruption. In concrete terms, this means that the central banks will have to keep their key interest rates (which they control directly) at very low levels, while trying to prevent any significant rise in bond yields (which they do not control directly). In short, they will try to control the entire yield curve, as the Bank of Japan has been doing for several years.

As a result, traditional money market and bond investments have little appeal. Assets in money market and bond funds increased again in 2020. This is understandable in the context of a global pandemic with many prevailing uncertainties. The fact remains, however, that against a backdrop of persistently low interest rates, money market and bond investments are not a satisfactory solution for capital in need of investment opportunities that can plausibly deliver a high enough real return to fund retirement or other savings needs. On the contrary, the returns on these fixed income investments are almost certain to be negative in real terms (i.e. adjusted for inflation). Preserving, and hopefully increasing, purchasing power should however be the ultimate goal for most types of savings.

It therefore follows that investments generally considered as the least risky, because they are the least volatile, should gradually be abandoned in favour of riskier, more volatile, investments. At the same time, volatility might no longer be the best definition of risk. Clearly, if central banks succeed in controlling the yield curve, government bond prices will not move much and their volatility will therefore remain low. However, this does not obviate the fact that inflation will erode their purchasing power over time. This gradual loss of purchasing power will obviously be less visible than a temporary drop in equity prices. However, as long as risk and volatility continue to be equated, the inevitable conclusion is that investors will need to be prepared to accept more risk to have the possibility of continuing to generate a satisfactory return. This is the logical consequence of the penalisation of secure savings and the suppression of expected returns from secure debt.

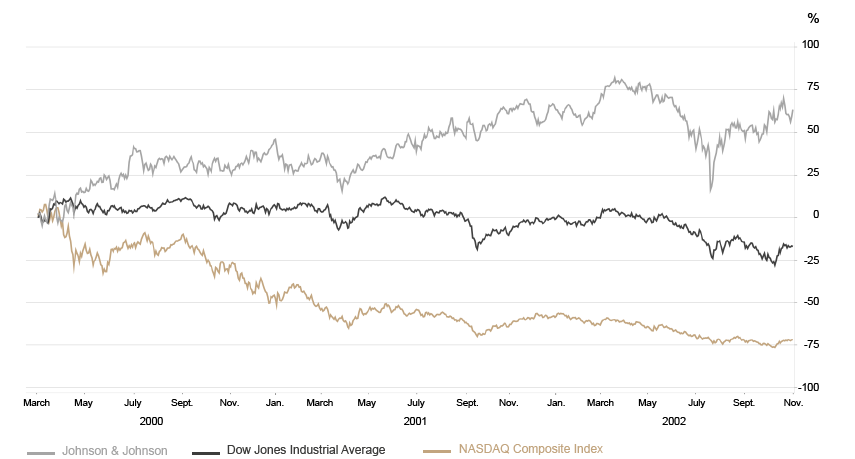

In most traditional portfolios, abandoning money market and bond investments (or at least reducing their allocation) means increasing the weight of equities. But the valuation multiples of equities are now high, and in some cases even close to their record levels. How can this dilemma be resolved? The answer that makes the most sense to me is to stop generalising and treating equities as a homogeneous class. Within the equity markets, there are clearly some segments that are now overvalued – or even absurdly valued. Likewise, there are also segments that have not been the target of investor frenzy and whose valuation remains reasonable. In this respect, the situation slightly resembles what happened at the beginning of this century. At that time, the market was expensive because the valuation of TMT (Technology-Media-Telecoms) stocks had become absurd. When the TMT bubble burst, the Nasdaq index, dominated by these stocks, lost nearly 80% of its value between March 2000 and October 2002. Over the same period, the Dow Jones index, with a much smaller concentration of tech stocks, ‘only’ lost 25%. Meanwhile, a company like Johnson & Johnson, which was neglected by investors before the bubble burst and was therefore relatively cheap, saw its stock price appreciate by over 70%. (That is where the comparison with the situation 20 years ago stops. At that time, high valuation multiples reflected excessive growth expectations, especially for the TMT segment. Today’s high multiples reflect a low-interest-rate environment. In technical jargon, the equity risk premium was negative back then, today it is in line with its historical average.)

Performance of the Nasdaq, Dow Jones Industrial and Johnson & Johnson between March, 2000 and October, 2002

Source: Bloomberg

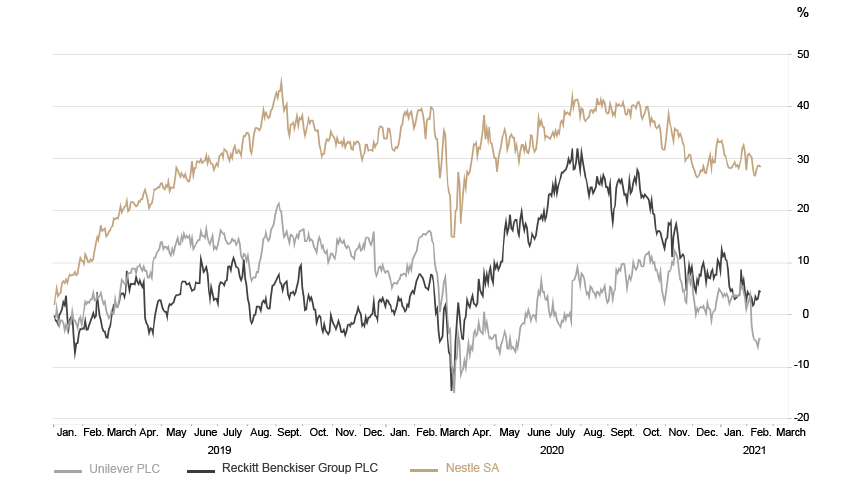

So what are the neglected segments within the equity markets today? Some will say they are mainly the ‘value’ style sectors, like banks, commodities and highly cyclical stocks. While there are certainly opportunities to be found in these sectors (starting with energy), the fact is that they are often sectors facing serious structural problems, problems that have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. A more interesting, and qualitatively significantly superior, path seems to me to be that of more defensive sectors (defensive in the sense that the results of the companies in these sectors are less sensitive to the economic climate), which pay sustainable and rising dividends and offer a degree of protection against inflation (since companies in these sectors usually have more pricing power given the essential nature of their products). These sectors should benefit from cash inflows as investors in search of recurring income switch out of bonds. The sectors that spring to mind are consumer staples and healthcare. Here, there are no signs of a bubble: the share prices of stocks like Nestlé, Reckitt Benckiser or Unilever are not much higher than they were two years ago (in the case of Unilever, the price is even lower). But even beyond these two sectors and those associated with the value style, it is still possible to find companies whose valuation is not too high, especially in a low interest rate environment. This is particularly the case for investors who are prepared to venture outside of the traditional markets and look at Asia and emerging market countries, for example. Such a selective approach has nothing to do with trying to beat a particular index. This should be seen as a good thing since the constraint often imposed on fund-managers to outperform an index over a relatively short period of time is in direct conflict with what should be their prime objective: protection of the capital entrusted to them and its associated purchasing power.

Performance of Nestle, Reckitt Benckiser and Unilever since the end of 2018

Source: Bloomberg

Lastly, a word about gold. The scenario described above towards which we seem to be heading – expansionary fiscal policies financed by money creation – is favourable to gold in that it will lead to a debasement of paper currencies. In the meantime, the yellow metal benefits from negative real interest rates and offers protection against the risk of inflation returning. In the past, gold has also generally (but not always) protected a portfolio during the equity markets’ more challenging phases. In portfolios with a strong equity weighting, this would represent a significant advantage.