No miracle solution

Through their actions, the central banks are making life hard for savers who are not prepared to take risks and who traditionally favour money-market investments rather than term deposits or savings accounts. The yield offered by these investments is now close to zero. Some banks are even considering introducing negative rates, mirroring the rate the ECB offers for their own deposits. Where a bank offers higher yields on this type of investment, savers would be right to question its solidity.

Investor's dilemma

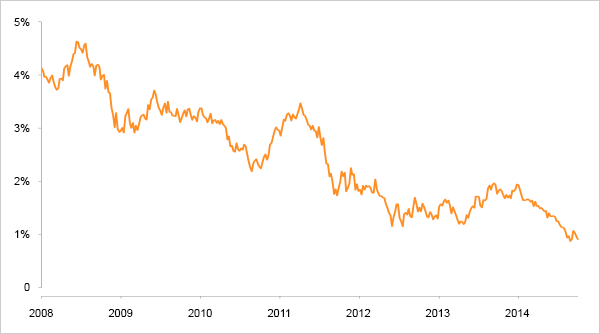

The prudent saver's logical reaction is (and has been) to abandon money-market investments and opt for bonds instead. These are a little more risky (unlike a savings account, the price of a bond, and therefore of a bond portfolio, can fluctuate) but since a bond has a fixed maturity, the saver can console himself with the thought that 100% will be redeemed on maturity. However, this reasoning is only valid if the issuer of the bond is sound – something that investors who bought bonds issued by Greece or General Motors recently discovered. This reflects a new dilemma for the saver: the yield offered by high-quality bonds is extremely low (Germany has just issued a 10-year bond with a coupon of 1%). To get higher yields, you have to make major concessions in terms of debtor quality (or invest in more exotic currencies and assume the currency risk). But even in this case, the yield is not very attractive and not on a par with the risk incurred.

German 10-year governement bond yield

Risk: Volatility

This is where equities come into play. The prudent saver will immediately say they are too risky, especially after their good run in recent years. And it is true that equities are risky if we take volatility as the measurement of an investment's risk. A share price fluctuates a lot more than a bond price. The value of an equity portfolio can rapidly drop 10-20%, or even more, without the fundamentals of the companies it represents necessarily having changed. An investor who buys shares has to accept this volatility both financially (not be constrained to sell at the worst moment) and emotionally (not panic at the worst moment).

Risk: Loss of capital

However, in today's climate, we might well wonder whether volatility is actually the best way to measure risk. In an era dominated by a number of structural problems, there is also a question about the risk of a permanent loss of one's capital (or at least a significant portion of it). This risk can be eliminated to a large extent in the case of equities by picking shares of high-quality companies and buying at a reasonable price. But the risk is much higher in the case of lesser quality bonds, if only because companies that issue a lot of bonds are by definition likely to be heavily leveraged.

Risk: Loss of purchasing power

There is also the risk of loss of purchasing power. EUR 100,000 in a savings account may well still be EUR 100,000 five years later but will probably buy fewer goods and services if the cost of living continues to rise.

Quality and dividends

So what are the options? There is no miracle solution. A saver not wanting to or not being able to bear the volatility of equities has to be content with very low or even zero yields and accept a possible loss of purchasing power. He / She should resist the temptation to buy poorer quality bonds on the pretext that they offer a slightly better yield. A saver who is prepared to accept the volatility of equities (this presupposes a sufficiently long investment horizon) should take the plunge and invest part of his/her assets in shares ofgood quality companies, focusing among other things on the dividend. Whereas (in the short term) the performance of a company's share price is often disconnected from its fundamentals, the dividend it pays is directly influenced by them and is therefore a lot less volatile (provided the company in question has been carefully selected). For an investor looking for regular income, dividends offer an alternative to interest.