Understanding the euro crisis

To understand the euro crisis, it is helpful to remember that at the outset, economists were far from unanimous in their support for a European single currency. At the time, the political authorities did not take account of their arguments, preferring to brandish them as anti-European.

The arguments put forward at the time were for the most part based on the works of two Nobel economic prizewinners, Robert Mundell and Jan Tinbergen.

The optimal currency area theory

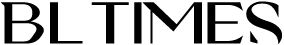

Robert Mundell pioneered the optimal currency area theory, an area which would fulfil the four criteria listed in the table below:

Based on the table, the conclusion is that the eurozone, unlike the United States, meets practically none of the necessary criteria for an optimal currency area. Labour mobility is low (partly due to language barriers), the labour and product markets are highly regulated, and there are no fiscal transfers between eurozone countries.

The Tinbergen theory

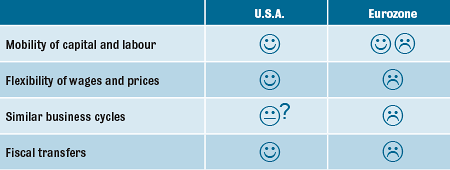

Jan Tinbergen, winner of the first Nobel prize in economics, defined a rule that for each economic policy objective pursued by a state, at least one policy instrument is needed. In concrete terms, this means that if a state has three economic objectives, it must have at least three separate instruments to meet these objectives. And in practice, states generally have three main objectives- price stability

- full employment (or at least the highest level of employment possible)

- and a relatively sound external trade balance.

Before monetary union, the Tinbergen rule was met by the countries which are today members of the eurozone.

To meet the above three objectives, these countries had four instruments:

- monetary policy (raising or lowering interest rates),

- money supply,

- (expansionary or restrictive) fiscal policy ,

- currency (which could go up or down).

Source: Strategic Economic Decisions

Since the introduction of the euro, the Tinbergen rule has ceased to be met. The eurozone countries have lost the control over their monetary policy, their money supply and their currency. The only tool left is fiscal policy (and even here, budget austerity in the peripheral countries means that these countries do not have the control over their fiscal policy) to meet their objectives. This is impossible and the results are less far from optimal.

Source: Strategic Economic Decisions

Mundell andTinbergen: complementary theories

It is important to note that the Mundell and Tinbergen theories are complementary. If the countries making up the eurozone had for example similar economic cycles, the problem resulting from the Tinbergen rule would not be as serious, since what would be good for one country (in terms of fiscal and monetary policies, currency and money supply) would be good for the others. Similarly, if labour mobility in the eurozone was as flexible as in the US, the fact of a country no longer having recourse - due to their membership of the single currency - to the instruments mentioned above would be offset by the ability of the residents of a country experiencing high unemployment to migrate to a country with low levels of unemployment.

As noted at the start of this post, these economic arguments have been ignored by the political authorities. The single currency was allowed to be created and the first years of the eurozone were marked by the following developments:

- an expansionary monetary policy conducted by the European Central Bank, in response to the economic problems in Germany dating from the start of the century, but also due to the monetary policy conducted by the Federal Reserve in the United States;

- convergence of long-term interest rates of the peripheral countries towards the German level (why buy a German government bond offering a coupon of 4% if you could get 10% on a Greek bond in the same currency?);

- the peripheral countries experiencing abnormally low short and long-term interest rates, leading to:

- rising real-estate prices,

- rising consumer spending,

- increased public spending,

- stronger economic growth,

- rising labour costs,

- rising imports and falling exports.

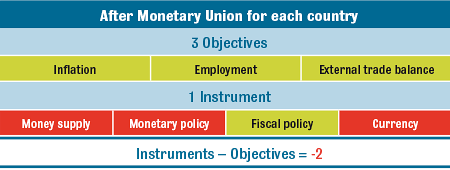

These last two points are very important. Since the introduction of the euro and up until the crisis, there have been huge divergences in labour costs (or to be more specific, in unit labour costs that adjust labour costs for productivity gains) in the north and the south. The upshot of this is that today the south is no longer competitive: in concrete terms, the countries of the south are dealing with high external deficits while the northern European countries are faced with high external surpluses. And external trade deficits implyforeign capital requirements.

Change in unit labour costs (wage costs adjusted for productivity gains)

Source: Datastream, Natixis

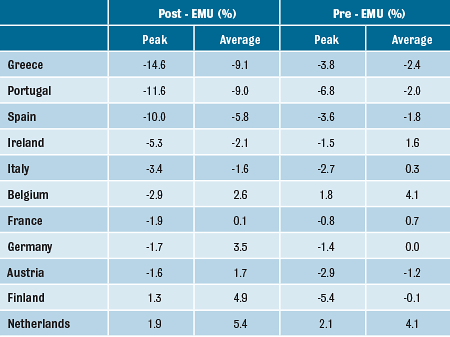

The table below speaks for itself. It shows the current account balance (as a % of GDP) of the eurozone countries in the 10 years preceding and the 10 years following the introduction of the single currency. In the 10 years prior to the introduction of the euro, Spain's average current account deficit was around 1.8% of GDP, and its peak was 3.6%. Since the introduction of the euro, Spain's average current account deficit has been 5.8% with a peak of 10%. Such a situation would not have arisen without the single currency which, while presenting a relatively balanced picture of the eurozone situation overall, masked what was happening within the member states. Of course, it is also worth noting that countries like Germany and Finland experienced the opposite trend in their current account balances.

In an environment in which the southern countries are no longer competitive, the Tinbergen rule is all the more important. In the past, these countries could have devalued their currency to restore competitiveness. Locked in the eurozone, they can no longer use this instrument.

Current account balance (as % of GDP)

Source: Nomura, Eurostat

Unhealthy interdependence between banks and states

The problems arising from the introduction of the single currency were further reinforced by two factors linked to the European banking system. First, regulations such as the Basel II framework have encouraged a situation of unhealthy interdependence between banks and states. Without going into detail, the Basle II rules strongly encouraged the banks to buy government bonds (and were as such very popular with governments which then had a captive source of refinancing).

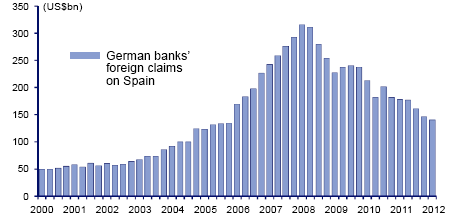

At the same time, the banks of the eurozone's northern countries naturally wanted to take advantage of the 'economic boom' in the south, especially as the euro had removed the exchange risk involved in their investments in this region. When the crisis erupted, they found themselves very exposed to these countries(adding to their existing risk on subprime in the US. The banks hardly covered themselves with glory in the crises and it is particularly frustrating that the authorities are not taking the measures required to ensure that an individual bank will never again be able to pose a systemic risk to the financial system.)

German banks' foreign claims on Spain (in billions of $)

Source: CLSA

The interdependence between bank and state and the huge exposure that the banks of the north have to the peripheral countries are only exacerbating the crisis in the eurozone and explain why it is so difficult to find a solution. Both factors are usually put forward by those who claim that a partial or total break-up of the euro would lead to economic catastrophe.

Eurozone caught in a vicious circle

The eurozone crisis is therefore made up of a range of crises:

- liquidity crisis (the inability of the peripheral countries to refinance themselves on the markets on reasonable terms),

- solvency crisis (the inability of the peripheral countries to generate sufficient revenue to honour their debts),

- competitiveness crisis (in the peripheral countries, with the exception of Ireland),

- fragile banking system,

with each crisis contributing to exacerbating the situation.

Steps taken to manage the eurozone crisis

... fall into four main categories:

- the dilution of the European Central Bank's quality criteria (it is accepting assets of increasingly dubious quality in return for the loans it grants to the banks);

- the huge capital injections by the ECB;

- the implementation of a bailout fund (currently being used by Greece, Ireland and Portugal), which provides capital to countries that are unable to refinance themselves on the market and in return imposes cuts in public spending and the obligation to engage in structural reforms;

- restructuring Greek debt

Impact of these measures...

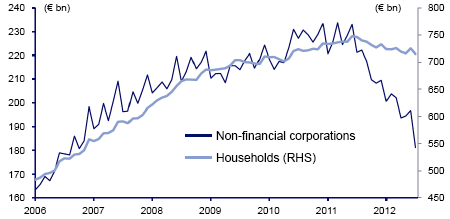

First of all, and regardless of what we think about its approach, it is important to point out that the ECB is not equipped to resolve a solvency crisis or a problem of competitiveness. It can only intervene to manage the other two aspects of the crisis, i.e. to help the peripheral countries to obtain financing, and to prop up the banking system. The second point is that the measures undertaken by the ECB often prove counter-productive. Given that such measures tend to calm the markets, they result in a certain complacency on the part of the political authorities. They also prevent the adjustments necessary by encouraging the banks on the periphery to borrow capital from the ECB (at a rate of 1%) that they then invest in the bonds issued by their country. Finally, the money that the ECB lends to the Spanish banks flies out again immediately given the lack of confidence in those banks.

Household and corporate deposits at Spanish banks

Source: ECB, CLSA

Budget austerity aggravating economic problems

Regarding the other measures, it is clear that the budget austerity imposed is aggravating the economic problems of the peripheral countries and making it even more difficult for them to service their debt (in the debt-to-GDP ratio, the denominator falls faster than the numerator resulting in a deterioration of the ratio).

Moreover, the capital from the bailout fund is used mainly to pay back existing debtors and does not make its way into the real economy. Also there is no private sector involvement. Obviously no private company is currently prepared to make huge investments in Spain, for example, if it doesn't know whether Spain will still be in the euro in two years' time. Regarding the restructuring of Greek debt, this has not gone far enough, especially as certain lenders, such as the European Central Bank, have not had to take losses on their positions.

The measures taken to date will enable the peripheral countries to refinance themselves (temporarily) on reasonable terms, either because they have taken refuge in the bailout fund (accepting or pretending to accept the austerity measures) and for the time being don't therefore have to resort to financing in the capital markets (Greece, Ireland, Portugal), or because the measures announced by the ECB have been sufficient to lower their financing cost in the market (Spain, Italy). These measures help to gain time but they do not provide a sustainable solution to the eurozone crisis as they do nothing to address the solvency or competitiveness issues.