Deflation: short series (2)

In the first blog post of this series, we familiarised ourselves with deflation as the result of gains in efficiency and a supply-demand shock. We saw that inflation has very seldom occurred in western industrial economies in the recent past, thanks to shifts in consumer spending behaviour and central bank monetary policy.

A spectre is haunting the world, the spectre of deflation

This has not always been the case. Prior to 1914, deflation was not unusual, due to the following reasons:

- the gold standard made active monetary policy practically impossible.

- there were still no central banks as we now understand that term, to conduct active monetary policy;

- extraordinary gains in efficiency, driven by the development of industry and agriculture at that time, as well as swift globalisation, e.g., through of railway and steamship travel.

Back then, those technologies were as exciting to people as IT, nanotechnology and biotechnologies are today and led to various debt-financed speculative bubbles. When the bubbles burst, they triggered crises of confidence, which, in turn, led to an across-the-board weakening in demand. This sent prices of goods and services down and, hence, led to deflation.

Probably the worst bout of deflation before the First World War occurred during the "Panic of 1873", which, incidentally, in some ways is reminiscent of the 2008/09 financial crisis. The Gründerzeit boom of the second half of the 19th century in Germany and Austria came with a bubble in the real-estate and equity markets, which led to an overheating of the economy. The bubble burst in 1873, which first hit all other securities markets worldwide. Later, more than 60 banks went bankrupt just in Austria and Germany. The subsequent crisis of confidence led to a global economic slump, which, because of the aforementioned demand shock, produced deflation.

From our perspective today, this bout of deflation and the ensuing depression is mostly regarded as having offset the excessive growth in the previous years and is considered stagnation. Its economic consequences from an overall historical perspective even tend to be regarded as "good" or "healthy".

However, the same was not true of the most recent worldwide bout of deflation – the global depression of the 1930s. Because of its duration, severity, and social and corporate impacts, the Great Depression has remained fixed in the collective memory, especially in the United States. The Great Depression has not only been research by almost all important economists but also delved into by major American creative artists in various ways and manners.(1)

It was triggered by the steep price drops on US equity markets in September 1929. The date of 29 October 1929 in particular has gone down in history as "Black Tuesday". From its peak on 3 September 1929 to its trough on 8 July 1932 the Dow Jones index fell by almost 90%, to its initial level of 26 May 1896.

The stock market crash was naturally only a symptom and not the cause of the depression. Various theories on the cause have been developed to go with each conviction/economic school. I would like to outline both of the most popular explanations, as they:

- are the basis of the current general interpretation of developments;

- demonstrate the vicious circle that is tied into a long period of deflation;

- shed light on the current reactions of governments and central banks.

In my next blog post, I will discuss a third explanation for the Great Depression, the so-called "debt deflation" theory, as it is of special importance for our modern debt-based economies.

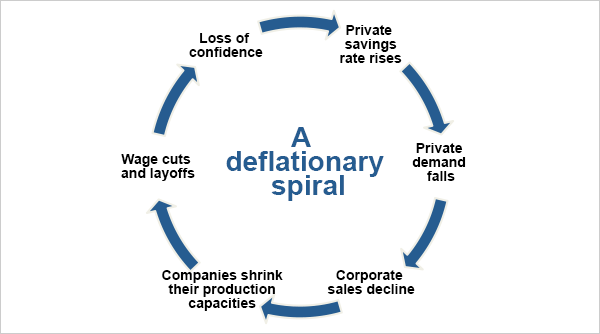

John Maynard Keynes came up with the theory that the general loss of confidence – caused, among other things by the stock market crash – led to a sudden increase in the savings rate and, hence, a decline in consumption. This undermined sales at companies, which then had to reduce their production capacities by cutting investment, laying off workers and cutting wages. This, in turn, led to an increased savings rate, driven by anxiety about the future.

Deflation spiral

If this deflation spiral is not broken, then over time the general expectation increases that prices will continue to fall in the future. It will then become worthwhile to hoard money instead of investing or spending it. This makes the downward spiral turn faster and faster.

Keynes' proposal to break the spiral: during downturns governments should reduce the private savings rate by taking on debt or cutting taxes, in order to offset shrinking demand. Most governments have heeded this advice since then, most recently to a great extent after the 2008/09 financial crisis. For example, the US government decided on a spending plan that sent its budget deficit from 1.3% of GNP in 2007 to more than 10% in 2009.(2)

At the same time as Keynes, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz developed the money-supply-based theory of "monetarism". In their view, inflation – and hence deflation, as well – is always a monetary problem. They therefore saw the main cause of the depression in the banking crisis. True, in the 1930s, countless equity portfolio-backed loans collapsed because of the stock market crash. About one third of all US banks, including a few large establishments such as the New York Bank of the United States, were forced to close their doors, and banks' equity capital dropped sharply. The money supply shrank by 35%, which kept many companies from receiving loans and from refinancing existing loans. This, in turn, pushed deflation to 33%.

Friedman and Schwartz therefore argued that the central bank could expand the money supply by cutting interest rates, injecting liquidity into key banks, and buying up government bonds to such an extent that consumers and companies would have enough money available for consumption or investment lending, to keep a recession from turning into a depression. Major central bank measures in recent years, particularly since the 2008/09 financial crisis, are based on these recommendations. However, during the Great Depression of the 1930s the US central bank was unable to use these methods, even if had wanted to, because of strict legal restrictions regarding the gold standard.

At first both theories raised controversy. Today a blended version has emerged and become mainstream, to wit: in normal times, demand and money supply should be kept on a stable path. If, however, the danger of a depression looms, as it did, for example, during the 2008/09 financial crisis, governments must adjust their tax and spending policies to prevent any demand shock, and central banks must steer their monetary policies – if necessary with the aforementioned means – in such a way that national economies and banks in particular are supplied with sufficient liquidity and capital.

As I mentioned above, in my next blog post I will explain Irving Fisher's theory of "debt deflation" and also go into why deflation poses a danger for our modern debt-based consumer society.

(1) For example, in the novel The Grapes of Wrath, by the Nobel Prize winner John Steinbeck

(2) Governments have ignored the second part of John Maynard Keynes' recommendation, namely that during economic upturns governments should reduce debt. As a result, most national economies' debt mountains have only grown. For many countries it is therefore increasingly difficult to take on new debt, in order to simulate growth in the event of a renewed economic slump.