Strong Euro or Weak Dollar?

The euro's strength continues to surprise. The single currency has not been particularly affected by the geopolitical climate, although it would have been reasonable to suppose that the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, to which Europe is significantly more exposed than the United States, would have weakened it against the dollar. A strong euro or a weak dollar? Many observers are surprised that despite US growth being markedly higher than the eurozone's, an unemployment rate half as high, and its energy cost significantly lower, the US currency has not appreciated.

A lot of noise about nothing

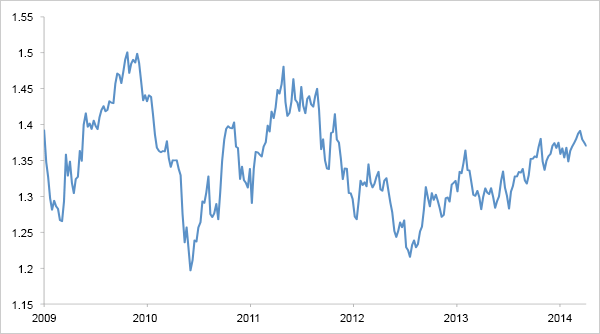

Before going further and looking for reasons for the dollar's weakness, we should first put it into perspective.The dollar's current level against the euro is not far from its average over the last five years. During this period, the EUR/USD exchange rate reached a high of 1.50 (October 2009 and April 2011) and a low of 1.20 (June 2010 and July 2012), with an average of 1.35. Since September 2012, this exchange rate has mainly fluctuated in a range of between 1.30 to 1.40. It hardly changed over the whole of the first quarter 2014, since the dollar ended the quarter at almost exactly the same level as it started.

Then, although we can talk about a relatively weak dollar when comparing it to the euro, that is not the case when we look at how it has fared against other currencies. The dollar's ‘trade-weighted' index, which shows how it has performed against the US's principal trading partners, has even gone up slightly over the last 12 months, a period during which the dollar appreciated notably against the yen and most of the emerging market currencies.

Exchange rate EUR/USD (5 years)

Source: Bloomberg

Factors supporting the single currency

So we should really talk about a strong euro rather than a weak dollar. Nonetheless, the euro's strength could seem surprising in a context marked by low economic growth and deflationary trends.

It is mainly due to the following:

- the increase in the eurozone's current account surplus

The eurozone's current account balance went from a deficit of 2% of GDP in 2008 to a surplus of 2% in 2013. The periphery countries' deficit disappeared as the weakness of domestic demand reduced imports while the success of their efforts to become competitive helped their exports. At the same time, the current account surplus in Germany continued to grow. Put simply, a current account surplus means that foreigners are buying more euros than Europeans are selling;

- renewed interest in the eurozone markets from foreign investors

Ever since the Chairman of the ECB, Mario Draghi, said in July 2012 that he would do whatever it takes to save the euro, foreign investors have flocked to the eurozone's financial assets, evidenced particularly in the performance of the periphery countries' stock and bond markets. This has created additional demand for the single currency;

- the central banks' balance sheets

While the Federal Reserve's balance sheet has continued to expand, that of the ECB has been shrinking since 2013. This reduction is due to the European banks' repayment of the LTRO (Long Term Refinancing Operations granted by the ECB to the banks to improve their financial position) and by the fact that the ECB has not (yet?) embarked on quantitative easing. Generally speaking, it is also worth pointing out that since the Internet bubble burst in 2000, the Fed has tended to pursue an anti-deflationary monetary policy whereas the ECB has been significantly more conservative in its approach.

- other factors

Among these are predominantly China's sale of US treasury bonds and, more generally, the reduction in the Federal Reserve's custody holdings of Treasury securities.

Towards a weaker euro?

We should therefore also look at these factors to identify a possible trend reversal for the euro.

The first factor, the increase in the eurozone's current account surplus, is set to continue. The weakness of domestic demand will continue to weigh on European imports. The yen's example in the 1990s shows that the economic doldrums do not necessarily lead to a weak currency. The Japanese currency appreciated significantly over this period despite very weak growth, much lower than that seen in Europe or the United States. In just the same way as we are currently seeing in the eurozone, the weakness of domestic demand contributed to ever bigger trade surpluses, which in turn fed through to stronger yen.

The second factor, foreign investors' interest in the eurozone's financial markets, is by definition impossible to predict. At present, it remains sustained, with many commentators arguing that the periphery's markets are still cheap.

The third factor, changes in the US and European central banks' monetary policies, is often cited as liable to strengthen the dollar in the coming months. The idea behind this is that the Federal Reserve is currently abandoning its quantitative easing process and could start raising its key interest rates as early as the second quarter of next year. By contrast, the ECB might actually start its own quantitative easing programme should the deflationary trends within the eurozone intensify - especially as the recent pronouncements by the President of the Bundesbank have been interpreted as a sign that the German bank would no longer be opposed to such measures. Aside from the possibility of quantitative easing, the recent pronouncements from members of the ECB show that the central bank is becoming concerned by the euro's strengh which is adding to the risk of deflation.

However, any tightening of American monetary policy from the second quarter of 2015 is far from certain. Some of the factors that stimulated US growth in the second half of 2013, corporate restocking and exports, are starting to fade. The main problem for the US economy is the lack of any increase in disposable income, given the dominant role played by personal consumption in US GDP. It should also be noted that an increase in interest rates would raise the cost of servicing the debt and pose a problem for fiscal policy.

As regards the other factors, China's sale of US treasuries seems to be explained by the Chinese authorities' determination to reduce the proportion of the dollar in their currency reserves. However, this is a long-term objective which does not preclude China from buying US treasuries from time to time.

Still confused, but on a higher level

Analysis of these different factors does not enable us to reach a clear conclusion on the future of the EUR/USD exchange rate. Obviously, trying to predict what will happen to currencies is a somewhat futile exercise. Unlike equities which represent stakeholdings in companies that it is possible to put a value on, currencies have no intrinsic value. It is therefore difficult to say that a currency is over- or under-valued. Theories like that of purchasing power parity try to do this but only really work in the (very) long term. In the case of a currency like the European currency, there is the additional problem that the eurozone includes countries as diverse as Germany and Greece and that the euro is perhaps too low for Germany and too high for Greece.

To hedge or not to hedge?

The US equities in our portfolios are generally those of international companies, realising a significant proportion of their revenues outside the United States. Since a depreciation of the dollar increases the profits (expressed in USD) of these companies, they offer a sort of natural hedge against such a depreciation. We do not therefore hedge the currency risk of these positions. However, we do (partially or totally) hedge this risk on our positions in US government debt.

Finally, it should be noted that in extreme situations, until proved otherwise, the dollar will retain its status ofsafe haven. Among the biggest risks that we can currently identify is that of a renewed deterioration of the situation within the eurozone, notwithstanding the apparent calm that has reigned over the last 18 months or so. If this were to be the case, the dollar could be expected to strengthen. Similarly, the dollar's status as reserve currency means that changes in the US current account balance are partially the reflection of expansion or contraction phases in the global economic situation. During expansion phases, the US current account balance tends to post an increasing deficit (leading to a weaker dollar), with the opposite being true during contraction phases (leading to a stronger dollar). Most analysts are expecting the global economy to pick up this year. The numerous structural problems currently present do however mean that these expectations could be disappointed with a negative impact on the equity markets. In a diversified portfolio, the dollar therefore also represents something of a hedge against the equity risk.