Investment strategy 2019

To some extent, 2018 was a mirror image of 2017 on the financial markets. Twelve months ago, the markets had just ended a fairly exceptional year which saw most indices increase by over 10% in local currency. One year on, the situation is completely the reverse and it is hard to find an index that has not lost at least 10%.

To some extent, 2018 was a mirror image of 2017 on the financial markets. Twelve months ago, the markets had just ended a fairly exceptional year which saw most indices increase by over 10% in local currency. One year on, the situation is completely the reverse and it is hard to find an index that has not lost at least 10%.

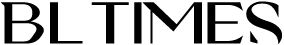

Stock prices fell in 2018 despite decent corporate earnings growth. For example, in the United States, a 20% increase in earnings per share for Standard & Poor’s 500 companies produced a 6% decline in the index. Last year’s contraction in multiples was one of the sharpest recorded in the last 30 years. It was partly due to tangible factors, like monetary policy tightening in the United States, but also to less tangible factors, like the change in the way investors interpreted the economic environment – having started out as optimists they ended the year with a fairly dismal view of the economic outlook. Towards the end of the summer, they concluded that even the US economy would not escape the reality of economic slowdown. Hence the US market’s nosedive in the fourth quarter. Clearly, geopolitical events did nothing to improve the situation, first up being the trade conflict between the United States and China.

Equity market performance in local currency since January 2018 (in USD for Asian markets)

Source: Bloomberg

2019 has started off with a huge number of uncertainties. These uncertainties concern the global economy as much as the attitude of the central banks and the geopolitical situation. It would therefore be a mistake to adopt too rigid an investment strategy. Instead investors should be prepared to adjust their strategy as necessary during the year. The sharp rebound in share prices in the first three weeks of January has already caught many investors on the hop. Given that investors tend to have a mindset conditioned by the markets’ recent performance, their confidence in equities was shaken at the end of last year and they may have begun this year too pessimistically.

However, despite the markets’ current upturn, the watchword at the beginning of this year should be capital protection rather than capital appreciation. The first half of the year could see a significant wave of downward revisions of economic and earnings forecasts. It will be difficult for a sustainable recovery to materialise on the equity markets while this process continues. If the Federal Reserve resorts to less aggressive monetary tightening (or even no further tightening), this could prop up the markets as long as it is not accompanied by too severe an economic slowdown.

More generally, we have reached a stage where the central banks’ determination to normalise their monetary policies has come up against a first major obstacle, a cyclical slowdown in economic activity. This will lead to greater volatility on the financial markets. The Federal Reserve's change of tone shows that the central banks are still listening to the financial markets. Nevertheless, it will be harder for them to react to a slide in equity prices since the macroeconomic environment has changed a little. The elimination of the negative output gap (the difference between actual and potential growth) and the associated deflation risk makes it harder to justify unorthodox monetary policies. And anyway, what tools would the authorities have at their disposal in the event of a fresh sharp deterioration in the economic situation? Their interest rates are now significantly below pre-2008-crisis levels, balance sheets have swelled and government debt is way higher than it was back then. It is therefore possible that in the event of a marked economic slowdown, the central banks would resort to even more unorthodox measures, but it is not at all certain that this would have the same positive effect on the financial markets. After all, if resorting to unorthodox policies did nothing to enable an overhaul of the global economy and set it on a sounder footing before, why would resorting to even more unorthodox policies enable this to happen now?

However, it would be counter-productive to adopt an overly negative attitude to the equity markets. As noted above, the contraction in multiples last year was massive. A more difficult environment would therefore seem to be at least partially factored into current equity market prices. At the same time, interest rates are still at very low levels and some elements at the root of the economic slowdown have been reversed and, in particular, the drop in oil prices and the decline in bond yields in the fourth quarter could stimulate consumer spending in the United States. If the current slowdown does not go too far and takes the form of a soft landing for the economy and a more moderate pace of growth, similar to that seen between 2011 and 2016, and if at the same time the Federal Reserve stops its monetary tightening, the markets would react very positively. The fear of an imminent recession in the United States seems premature at present. Nonetheless, it is notable that nowadays economic cycles seem increasingly to be a result of what is happening on the financial markets rather than the opposite – the 2001/2002 and 2008/2009 recessions were the consequence of equity market collapses. It is a bit surreal to imagine the scenario of a significant slump on the equity markets leading to a recession which would then justify why share prices had fallen in the first place.

Notwithstanding the contraction in multiples in 2018, the valuation of most markets remains high overall, especially as company profit margins are well above average. Two factors have marked the upturn in equity prices since 2009. First, the rise in equity prices has been much higher than the increase in earnings, generating an expansion in valuation multiples. Second, the increase in earnings has itself been considerably higher than the increase in sales revenues, reflecting an increase in company profit margins. In the United States, a third factor comes into play: since companies have engaged in massive buybacks of their shares, the increase in earnings per share is substantially greater than the increase in earnings. These share buybacks have often been financed by debt and, as a result, the debt levels of US companies have risen significantly and are now at worrying levels, especially if the large tech companies which are sitting on huge cash piles are excluded from the statistics.

Ultimately, it is valuation multiples which to a large extent determine future returns. For example, let’s consider a company like Nestlé which is currently trading at around 20 times earnings. Imagine that it manages to increase its earnings by 5% per annum over the next 10 years. If in 10 years, the market is still prepared to pay 20 times Nestlé’s earnings, the company's share price will be CHF 135 and an investor will have seen an annualised return of 5% (plus the annual dividend). If, on the other hand, the market is only prepared to pay 15 times earnings, the share price will be nearer CHF 100 and the annualised return will only be around 2% (+ dividend). Conversely, in a scenario where the multiple that investors are prepared to pay goes up to 25, the annualised return would be 7.5% (+ dividend). In each of these scenarios, Nestlé is the same company with the same earnings growth; the only thing that changes is the multiple that investors put on these earnings. As indicated above, this multiple depends on tangible elements like the level of interest rates as well as less tangible (and less predictable) elements linked to the state of mind of investors and how they are viewing things.

From the foregoing, it is clear that to have the odds stacked in your favour and not be at the mercy of a potential change in investor psychology, it is better to buy when valuation multiples are low. The long bull market in the 1980s and 1990s started in 1982 with very low multiples, since the inflationary period of the 1970s and the resulting sharp rise in interest rates had led investors to forsake equities. The decline in inflation and interest rates then caused an expansion in valuation multiples, an expansion which was also made possible by favourable geopolitical developments such as the end of the cold war and globalisation. Added to this, the demographic structure of the global population in industrialised countries was conducive to an increase in available savings. These elements are currently reversing: the potential for interest rates to increase seems exhausted, the return to policies promoting the national interest over international cooperation is introducing economic and geopolitical risks, and the demographic structure of the population has reached a stage where it threatens to negatively impact available savings. Over the long term, valuation multiples therefore have a strong chance of declining and it will be all the more difficult to generate high returns from equities.

S&P 500 P/E and normalised P/E ratios since 1927

Source: Bloomberg, S&P Dow Jones Indices

Even in difficult markets, it is possible to invest intelligently in equities, provided one has a very rigorous stock-selection process which can stay the course and a sufficiently long investment horizon. As far as we are concerned, the approach consists (and will always consist) of selecting high quality companies which have a sustainable competitive advantage enabling them to generate a higher return on capital employed and present a solid balance sheet reflecting their self-financing capacity. This type of stock is often unpopular nowadays on the basis that it is expensive. While it is true that the valuation multiples of such companies are higher than average, their premium could go up even further if the economic outlook continues to deteriorate. In the current context, the priority must be on relatively defensive companies with good earnings visibility and a solid platform for their dividend pending a return to good quality cyclical stocks whose share prices have already fallen considerably in many cases.

At the beginning of the year, it is often customary to highlight the merits of one region over another. Such recommendations are often based on valuation differences between regions. But it is important to note that these valuation differentials are mainly explained by the composition of the indices. An index like the S&P 500 is quite simply of better quality than the majority of the European indices in which sectors and companies with structurally low margins often have a significant weighting. In terms of valuation, an argument can nevertheless be advanced in favour of the Asian markets which suffered last year from the strength of the dollar, the rise in bond yields in the United States, and uncertainties over China. The Asia region (ex Japan) index is back at the level it was at 11 years ago and, in relation to companies’ book value, is trading at a significant discount to its average for the last 20 years. Meanwhile the Japanese market continues to benefit from several attractive attributes: the profitability of companies is structurally improving, they are much less-leveraged than their US and European counterparts, and their valuation is attractive.

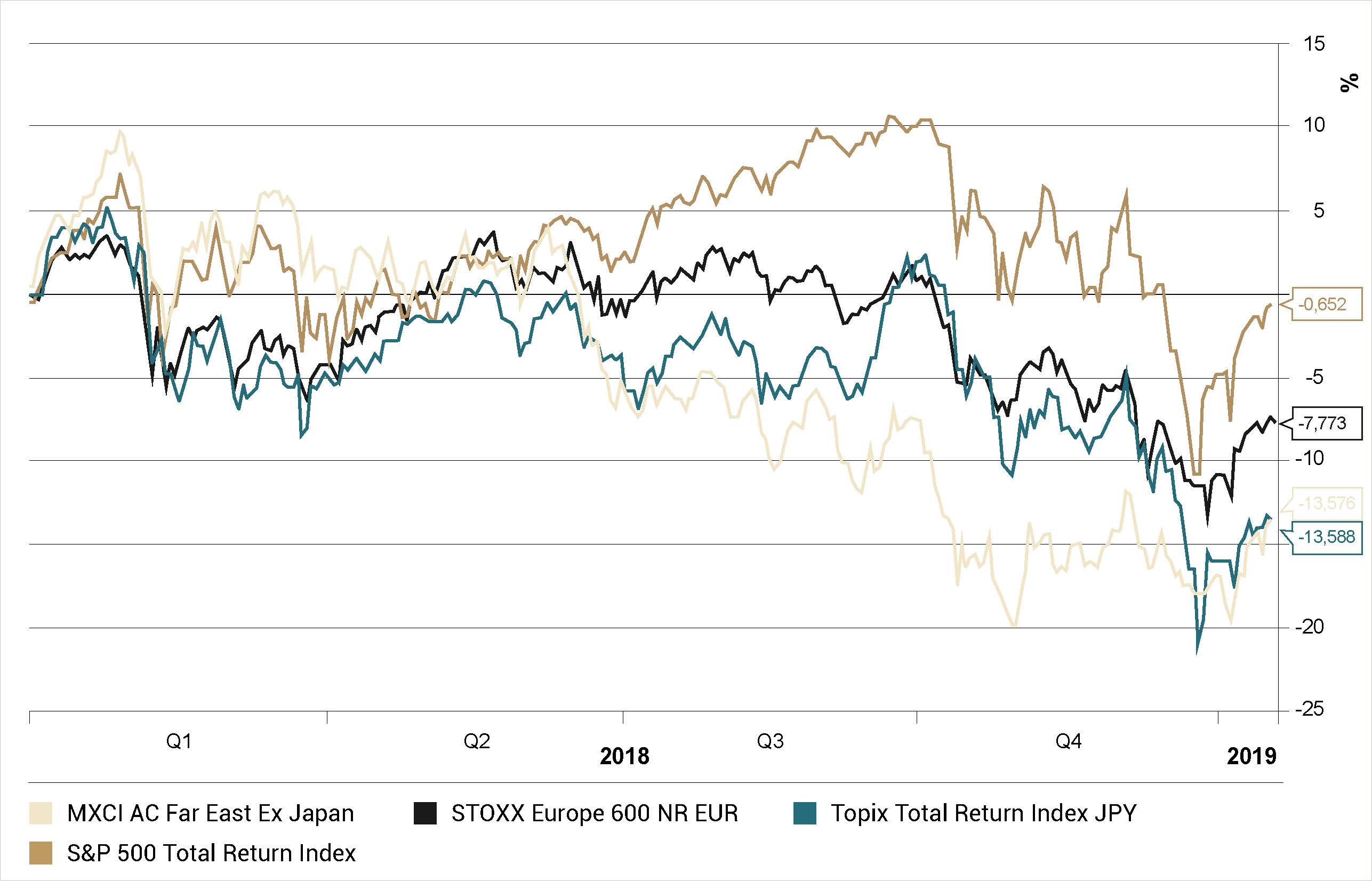

MSCI AC Far East ex Japan index

Source: Bloomberg

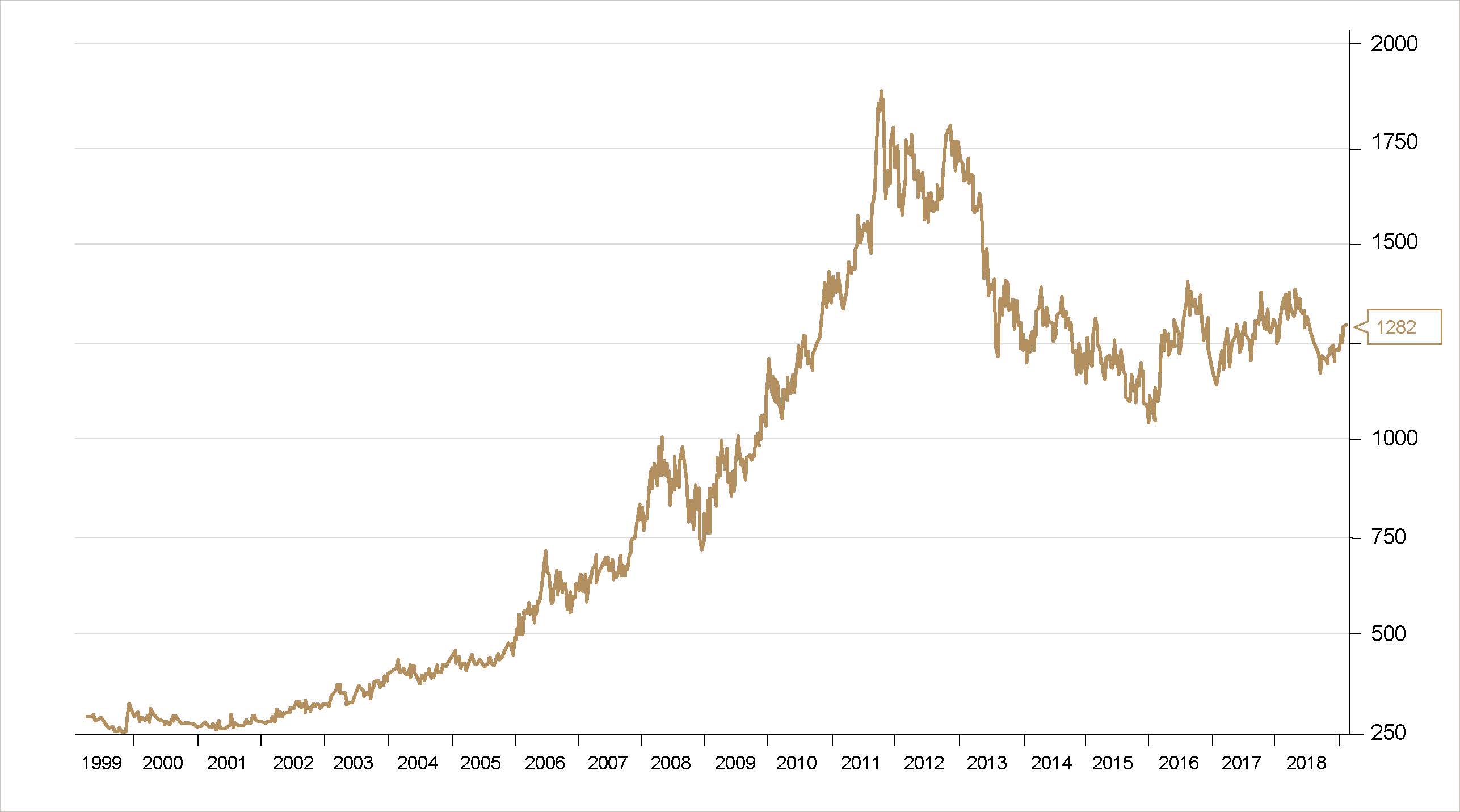

During the market slump in the fourth quarter of 2018, gold and high-quality government bonds showed they still have a place in a diversified portfolio to hedge against equity risk in the event of an increase in risk aversion. For government bonds, this may no longer be the case in future. With the sharp increase in public debt, it is becoming increasingly difficult to describe government bonds as quality assets. More fundamentally, a more inflationary regime would make the correlation between equities and bonds positive again, as happened at the beginning of February 2018 when fears of a return of inflation drove down equity and bond prices. For the time being, it would seem premature to bet on such a return, but investors would be wise to remain on their guard. Meanwhile, the slowdown in the global economy is likely to be beneficial to long-dated US Treasury securities.

Gold price

Source: Bloomberg