Corporate debt: Glencore, VW, Petrobras…

The corporate default rate is at its highest level since 2009. In its latest study on 30 November (1), Standard & Poor's reported a sharp increase in the number of companies defaulting in 2015: 101 issuers reneged on their obligations. The last time the figure was so high was in 2009.

Corporate defaults piling up

The latest two companies failing to repay their debt are Uralsib, a Russian bank, and China Fishery, a global fish and seafood supplier. Among these hundred plus companies, only 21, i.e. one-fifth, are from emerging markets. Most are in Brazil and Russia. And the main sector concerned is oil and gas.

Corporate defaults by region (2004-11/2015)

Source: Standard & Poor's

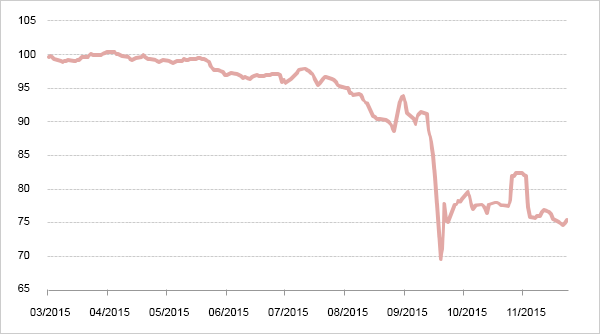

The latest news concerning Petrobras, Glencore, Valeant and VW has echoes of the crisis we saw in the 2000s on the corporate debt market. At that time, a number of companies were posting record debt levels which ended up causing them to default or engage in major debt restructuring: WorldCom, Enron, General Motors and France Télécom to name a few. We might well wonder whether the situation is different this time round. But if it isn't, does this mean the corporate debt cycle is at tipping point? Are we about to see major debt restructurings? Let's look at the history of the price of the Glencore 1.25% bond maturing in March 2021. In 2012, Glencore launched its acquisition of the Swiss mining company Xstrata. In 2013, it took over the Canadian trader Viterra and in 2015 embarked on a merger with Rio Tinto. The latter did not succeed.

Price of Glencore 1.25% bond maturing 03/2021

Source: Bloomberg

Déjà vu of the 2000s

We can all remember the names of companies that made the headlines just over ten years ago: AOL Time Warner, Vivendi Universal, WorldCom, Alcatel, Nortel, Lucent, Cable & Wireless, etc.

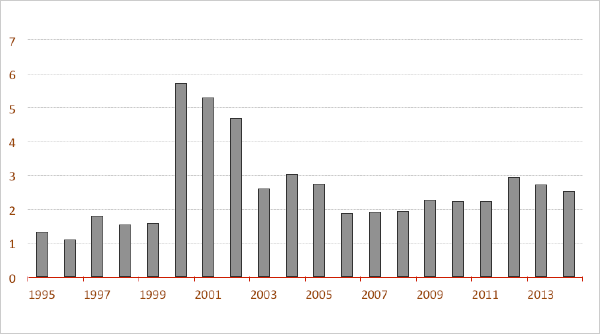

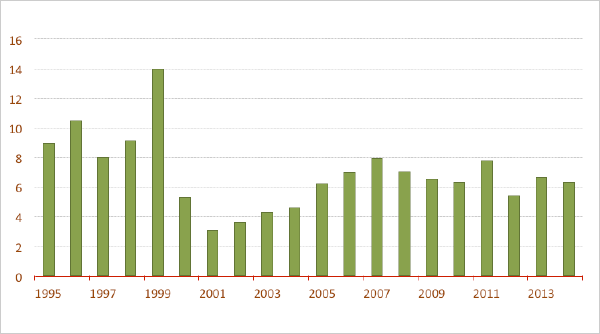

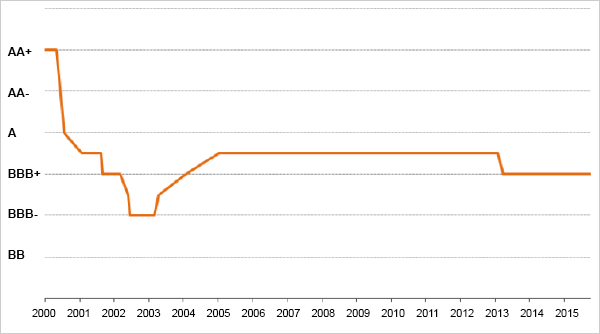

At the end of the last decade, in the wake of the dot.com bubble bursting, the telecoms sector engaged in a fresh cycle of deleveraging. The French operator Orange, formerly France Télécom, is an instructive example. AA-rated in 2000, the company saw a steady downgrading of its rating in line with its deteriorating balance sheet (due to a series of acquisitions including the takeover of mobile phone operator Orange from Vodafone). Having become one of the most debt-laden companies of the time, it flirted with junk status in July 2002 when its rate was ultimately cut to BBB-. That was when Thierry Breton was put in charge of the company and proceeded to turn its finances around over the following two years. The following graphs show the company's net debt-to-EBITDA ratio (2), the interest coverage ratio and its S&P rating.

Orange (France Télécom): net debt-to-EBITDA ratio

Source: Bloomberg

Orange (France Télécom): EBITDA-to-interest coverage ratio

Source: Bloomberg

Orange (France Télécom) rating history

Source: Standard & Poor's

Primary sector debts and bank loans

Many companies are now posting debt and liquidity levels equivalent to those of the telecoms sector in the early 2000s. You only have to look at the sharp increase in global issue volumes. In 2014, these came to 3.5 trillion dollars compared to 2.1 trillion in 2008 (3). Weak growth and the resulting deflationary pressures have led to a fall in earnings. The first companies to be affected are linked to oil and mining.

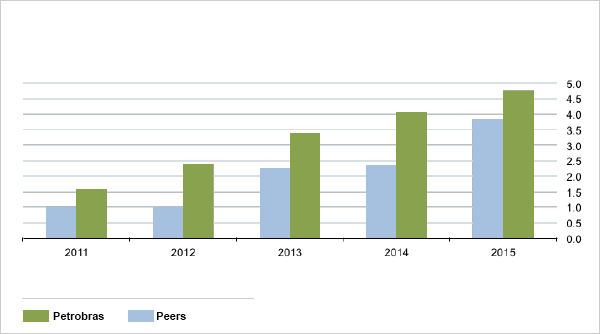

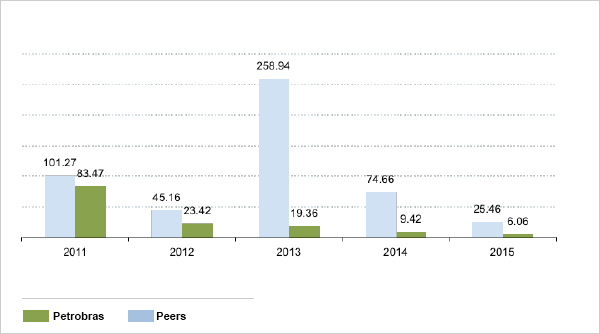

In emerging markets, Brazil and Russia have the greatest number of struggling companies. Petroleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) and the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) are a microcosm of the type of problems encountered on the corporate debt market: meltdown in commodity prices at the same time as an increase in corporate debt. Petrobras is a semi-public Brazilian and integrated energy company. BNDES is the Brazilian government's financial arm for funding various projects, ranging from agriculture to infrastructure, in Brazil and elsewhere but mainly in South America,. The following graphs show the comparative increase in Petrobras' debt versus its sector. These are the same ratios as those described above for France Télécom. The Brazilian company's debt levels are equivalent to those of the French phone operator in the 2000s and relatively worse than the sector as a whole.

Petrobras vs. Peers: net debt-to-EBITDA ratio

Source: Standard & Poor's

Petrobras vs. Peers: EBITDA-to-interest coverage ratio

Source: Standard & Poor's

The quantitative easing programmes being conducted in developed countries, in particular by the US Federal Reserve, led to massive financial inflows to emerging markets between 2008 and 2014. These flows encouraged an increase in bond issues and bank loans, for a total of nearly 7 trillion dollars (4).

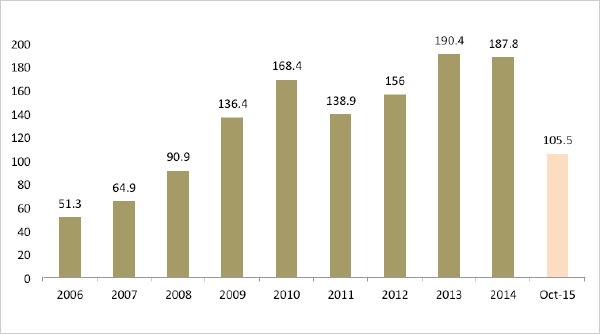

The case of BNDES illustrates the position of the corporate sector in emerging markets. Last year, after a continuous increase in its loan portfolio and with assets of 330 billion dollars, it was on the point of overtaking the World Bank as the world's second-biggest development bank after the China Development Bank. Unfortunately, it has suffered a sharp slowdown in activity this year, leading to a decline in disbursements. From January to October, the total amount of loans made by the bank came to around R$105 billion, which represents a drop of 28% compared to the amounts disbursed in the same period in 2014. From January to September, the bank's net income came to R$6.6 billion, which is 10.3% below the level recorded in the same period in 2014.

BNDES: disbursements in billions of BRL (Brazilian real)

Source: BNDES

Are we heading for a corporate debt crisis?

Potential fears for the corporate debt market would seem to be justified. Debt levels are high. Earnings are down. Monetary policies have taken or will be taking a less accommodative turn (despite the recent pronouncements by the President of the ECB). In particular, the return to a cycle of rising US interest rates coupled with a relatively strong dollar are looming over the market. If this does not happen, it would mean that the economic situation is not improving. Heavily indebted companies therefore find themselves between a rock and a hard place, especially those which operate in sectors most sensitive to economic cycles. For the next few months, it would be logical to expect them to have a decreasing capacity to pay down debt.

............................................................................................................................

(1) Default, Transition, and Recovery: Global Corporate Default Tally Tops 100 So Far In 2005, Standard & Poor's, 30 November 2015.

(2) This ratio can be interpreted as the number of years that it would take the company to pay down its debt based on its operating income.

(3) Corporate Shocks Show Swift in Credit Risk, Financial Times, 4 November 2015.

(4) Deeper Into The Red, Financial Times, 17 November 2015