Who buys bonds with a negative yield?

In view of the continued escalation of the banking crisis in Spain (Bankia was rescued last weekend with EUR 19 billion of government funds, the head of the Spanish central bank has (been) retired, in April alone deposits of EUR 31 billion were withdrawn from Spanish banks, according to Bloomberg, EUR 184 billion of problem loans (especially to property developers) still remain on the books of Spanish banks, etc.), it is understandable that investors are avoiding Spanish (government) bonds. It is therefore logical that yields on Spanish government debt are rising, both in absolute terms and also relative to the supposed stable core countries of Europe.

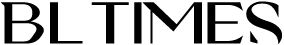

10-year Spanish government bond yield over the past five years

Differential from 10-year German government bond

(Source : Bloomberg)

However, in the markets, there appears to have been hardly any direct speculation against Spain. The risk of the ECB deciding over night to purchase massive amounts of Spanish government bonds is just too high. After all, it has done this before.

Although this would certainly lead to an increase in prices in the short-term, market intervention by the ECB would fundamentally be bad news for the owners of Spanish government bonds. Since – as has already happened with Greece – the ECB would be treated as a preferential creditor, non-governmental investors would receive less in a potential debt restructuring. ECB intervention in the market is therefore possibly another reason for selling Spanish government bonds.

Prior to any debt restructuring however, Spain would clearly first have to accept the EU rescue package. But for now, the politicians are (still) categorically ruling this out. Having said that, the same also happened in Greece, Portugal and Ireland until shortly beforehand. These countries actually accepted the rescue package when their respective 10-year government bond yields exceeded 7%. On Friday, the yield on 10-year Spanish bonds already exceeded 6.5% p.a. Things can therefore happen quickly.

If a country accepts the rescue package, this does not necessarily mean that it will restructure its debts (after all, Portugal and Ireland accepted the rescue package some time ago and have not restructured their debts). The example of Greece shows that whether or not this actually happens becomes a purely political decision and is therefore speculative. In the event, international institutions receive preferential treatment and it will be very painful for private investors.

An investment in Spanish government bonds therefore amounts to speculation that Spain manages to pull through either on its own, or with the rescue package but without debt restructuring, until the bond is repaid. As the acceptance of a rescue package, debt restructuring, and particularly the timing of these events are purely political decisions, no economic models exist for measuring this risk. I therefore wish every investor in Spanish government bonds the best of luck with timing!

Oh well, some commentators believe that Spain's acceptance of the rescue package would be the litmus test for European institutions. I don't share this opinion: Even though at approx. EUR 750 billion the debt of the fourth largest economy of the eurozone is about three times as large as the total debt of the three countries that have already accepted the rescue package, the ESM, or rather the EFSF, was specifically designed to also include Spain. As long as the crisis does not spread to another large economy (e.g. Italy), the rescue mechanism should be sufficient.

Germany set to borrow for free (www.FT.com 22/5/2012)

The immense problems in Europe beg the question how Germany, which may have to risk a lot of money as the saviour of the eurozone, can sell almost EUR 5 billion of two-year Federal treasury notes without having to pay any interest. During the week there were even buyers who purchased this bond with a negative yield. Why would anyone purchase a bond guaranteeing less money at maturity than was paid for it?

The answer is that the purchase of a German government bond, even with a negative yield, is an insurance against the break-up of the euro. A German government bond, which is later converted into "new Deutschmarks", would, as a result of the currency effect, virtually increase in value overnight by 40-50% compared to currencies in the peripheral countries. An investor who considers the break-up of the eurozone a possibility can therefore use the purchase of Federal government bonds to hedge against this risk. If I assess the probability of a break-up at 5% and the resulting loss in value of my investment portfolio (Southern European countries) compared to German government bonds at 50%, then I can insure myself with an investment of 2.5% in German government bonds. Even if the yield expectation for this 2.5% is negative, this is cheap insurance.

The situation in Switzerland is similar. There for example, during the past week, almost CHF 750 million of Federal 3-month treasury notes with a negative yield of -0.2% p.a. were sold. Is this the price of insurance against Switzerland severing its link to the euro?

Yes, because if Switzerland were to give up this link, then the CHF would certainly rise markedly in value over night.

No, since it would actually suffice to physically buy CHF or just to hold CHF in a bank account. The negative yield therefore reflects the difference in quality between a bank and the Swiss state.

Diversify in Quality

What action should therefore be taken today by an investor wanting to invest in bonds? An investment in crisis country government bonds is fundamentally a speculative investment, regardless of whether or not there is a break-up of the eurozone.

It makes little sense for an investor outside of the eurozone to invest in EUR bonds. The currency will remain under pressure until it finally becomes clear what is going to happen to the euro. Other investments, for example keenly priced shares in good quality companies, should protect this group of investors against a falling EUR. Following the same logic, it is advisable for euro investors to diversify broadly across foreign currencies. Part of the investment should definitely be in USD as the traditional safe-haven currency, even though the economic situation in the USA is not any better than in Europe.

An investor living and residing in the eurozone whose income and expenditure is in EUR should however not hold all of his investments outside of his reference currency; the currency market is inherently too volatile for this. Bonds are however not a viable and/or secure investment for such EUR investments. A "north-euro" investor would be better to invest his money directly in one or more "north-euro" banks. He would need to ensure that these banks don't hold significant investments in "the South". If he cannot find such a bank or does not trust "the banks", then the German government bond with a virtually 0% yield remains the least risky investment for him. In the main, this principle is also valid for "south-euro" investors. Such an investor must however be aware that a break-up of the euro would also result in the introduction of capital controls. To allow him to remain liquid in this instance, he must continue to hold some of his investments in his home country.

Some commentators think, by the way, that corporate bonds are more secure than government bonds. This is correct in so far that, on the one hand, the income of companies, especially if they are of good quality and established globally, generally exceeds outgoings (which at the present time cannot be said for any budget of a eurozone state); on the other hand, they can use the income to repay their debts. In addition, the yield they pay is slightly higher than that of low-risk government bonds. There again, it is totally unclear which new currencies the bonds of private issuers would be denominated in if there were to be a break-up of the euro. In my opinion, at 1.22% p.a. for example for Royal Dutch's five year bond, this denomination risk and the normal business risk is not adequately rewarded, even more so when compared to the money market rates of approx. 1% p.a. offered by most solid banks.

Since bonds are therefore generally less attractive, the only remaining option, as far as traditional cashinvestments are concerned, is shares. And, as a matter of fact, especially after the corrections of the last few days, there is a glimmer of hope here for investors. Please refer to Guy's article, published a few weeks ago, for further details. In this connection I would, especially for income-oriented investors, like to emphasise high dividends. Even during times of crisis, when share prices of many companies fell heavily (and have fallen currently), it is amazing how stable the dividend distributions have been before, during and after these times of crisis, and how stable they continue to be. If you can tolerate these price fluctuations, dividend-carrying investments are very attractive.

In conclusion, I hope you can remain level-headed when considering your investments and that you will not rush inito buying or selling without due consideration and reflection.