Equities: correction or bear market?

Since their peak last year, European and Japanese stocks have given up over 20%, and US stocks around 15%. That raises the question of whether the current downturn is not something more than just a correction and whether the markets could be on the brink of a much more slippery slope.

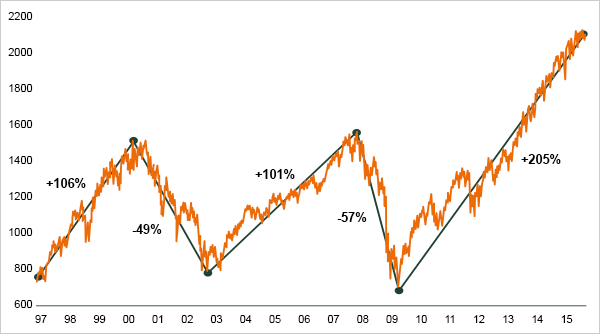

In the last twenty years, the equity indices have seen two serious bear markets: from the beginning of 2000 to the beginning of 2003 and from the end of 2007 to the beginning of 2009. In both cases, the decline was huge, and it took several years for the indices to recover their initial level, as shown in the following graph for the Standard & Poor's 500 index in the United States.

S&P 500 - 2 major bear markets in the last 20 years>

Source: J.P. Morgan

However, the root causes of the two bear markets lay in quite separate spheres. In 2000, it was due to excessive valuation. But note that this excessive valuation did not apply to the whole market but just to certain sectors, particularly those linked to the dot.com bubble. These sectors subsequently plummeted and even the share price of a high quality company like Microsoft fell by over 60%. Other sectors recorded a much smaller drop and the share prices of many companies even ended up higher in 2002 than in 2000. For investors, the best strategy at the beginning of 2000 would consequently have been to get out of the highly over-valued sectors. Since all valuation ratios were in the red for these sectors, this was perfectly feasible (what made things more difficult was the fact that these ratios were already in the red well before the start of the bear market, but this did not prevent these sectors from continuing to soar impressively and attract new investors who were convinced that a new era was dawning).

At the beginning of 2008, the situation was very different. There was no obvious bubble in any particular sector. The whole market was valued relatively highly but not to the point of justifying the ensuing nosedive. This time, the reasons for the tailspin lay in the economic and financial arena. Due to the securitisation of mortgages, the slump in the US real estate market permeated worldwide and took the financial system to the cliff-edge, at the same time prompting a global economic recession and the collapse of company profits. For investors, the best strategy would have been to get out of equities and seek refuge in government bonds.

How does the situation today measure up? There are no obvious similarities with 2000: there is no bubble in a particular stock market segment. At the same time the economic position seems significantly worse today.

There are some similarities with 2008. Falling oil prices have led to concerns about contagion from the energy sector, not unlike what happened in the real estate market eight years ago. The widening of interest rate differentials on lower quality bonds and the sharp increase in credit default swap prices in the banking sector were also factors in 2008.

But although there are some similarities with 2008, it is the differences that seem rather more significant. In some respects, today's situation is worse, and in some respects better. The factors that make it appear worse could be qualified as structural, and those that make it appear better, cyclical.

On the negative side, the global economy has never fully recovered from the 2008/2009 crisis. Even in the United States, the upturn that followed was unusually weak, especially if you consider the resources put into play to stimulate growth. Many structural brakes are continuing to weigh on the economic situation, starting with historically high debt levels, which have in fact increased still further in the last few years. The difference is that before 2008, the problem of excessive debt was largely a private sector problem whereas now it also affects the public sector.

The second notable difference versus 2008 is that the central banks have exhausted their conventional measures to deal with any further economic slowdown. Interest rates are at or near zero in almost all the industrialised countries. Having taken on a mission that is not really their role - to stimulate growth and create inflation - the central banks have started to embark on unconventional measures. As these measures have not produced the hoped-for results, the credibility of the monetary authorities has been undermined.

The economic model of recent decades, marked by credit-financed growth and monetary policy easing at the slightest setback, has therefore been called into question. At the same time, the necessary structural reforms and a coherent economic strategy are still severely lacking.

Today's economic situation calls to mind some aspects of the 1920 to 1950 era. Between 1913 and 1950, global economic growth was similarly weak, only around 1.9% per year (source OECD: Millennial Review), and social inequalities were huge, as is the case today. The 1929 stock market crash and ensuing economic crisis shattered confidence in the market economy. The result was excessive regulation which stifled all entrepreneurial spirit. At the same time, interest rates ceased to be determined by the interplay of supply and demand; instead they were set by the authorities. Capital flows were controlled and restricted. Most countries tried to stimulate their economy through competitive devaluations and were quick to introduce protectionist measures. Many of these trends are prevalent today.

A comparison with the 1920 to 1950 period also shows that for all the severity of the two bear markets in the 2000s, they were not a patch on the earlier period. It took 25 years for the Dow Jones index to return to its 1929 level (in nominal terms). When the two factors which determine equity returns - earnings growth and the Price/earnings ratio (the multiple that investors pay for these earnings) - decline, the damage is enormous. The stock price of a company with earnings per share of EUR 10 and a price/earnings (P/E) of 15 is EUR 150. If its earnings fall by 20% and its P/E to 10, the market value will be EUR 80, a decline of nearly 50%.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average index: 1921 - 1957

Source : Bloomberg

On the positive side, we should first note the massive price drop of the most important commodity for the world economy, oil. Since the second quarter of 2014, the oil price has plummeted by over 70%, creating a significant stimulus for the global economy. For comparison, the price of oil virtually doubled in 2007. In the past, any significant rise in the oil price has generally led to a deceleration in economic activity, while a decline has led to an acceleration.

The second major difference with 2008, is the level of interest rates. In 2008, an investor could still get a 4% return on a good quality bond or money market investment. Today, this return is near zero, if not negative.

Low interest rates increase the attraction of stocks over bonds and, all other things being equal, justify a higher valuation for equities. They also limit the problem of excessive debt since, although the level of debt is at a record high (in relation to GDP) in industrial countries, the burden of this debt is far from being so thanks to exceptionally low interest rates. It could even be argued that with negative yields currently on offer for a significant segment of sovereign bonds, governments would do better to increase their debt even further. In any case it is deplorable that governments are not putting their particularly low financing costs to good use to make productive investments which would have a multiplier effect on the economy.

Deciding whether the stock market falls of recent months are the start of a bear market or a correction depends on the degree of importance one places on structural elements (negative) versus cyclical elements (positive). Personally, I tend to be (extremely) concerned about the structural elements but think that the cyclical elements will prevail in the coming months. I also think that confidence in the central banks has been shaken but not (yet) lost. Since a further sharp stock market fall would jeopardise the central banks' targets, we cannot rule out the possibility that they will adopt increasingly extreme measures to avoid such a fall (buying corporate bonds? buying equities?...).

I would therefore give the benefit of the doubt to stock markets and lean towards the correction thesis especially as a number of factors which have been weighing on investor confidence in recent months have recently improved. China has clarified its foreign exchange policy, industrial production figures in the United States for January do not suggest a worsening of the manufacturing recession, Deutsche Bank's announcement of a buyback of some of its bonds has stemmed the slide in banking stocks, while oil prices and those of certain other commodities are showing signs of stabilisation.

But I have saved the most positive factor in favour of equities till last. Share prices have dropped by around 20% since the second quarter of 2015. But company earnings have not. Shares have therefore become less expensive and that means that their potential long-term return has increased.