Investment strategy 2020

After 2017, a year in which all the major asset classes posted significant gains, and 2018 in which they declined, 2019 was again a great year for the financial markets. Despite the continuing trade tensions between the United States and China, uncertainties over Brexit, the slowdown in global growth (in particular, a contraction of manufacturing sector economic indicators) and weak or even negative earnings growth, equity markets recorded their best performance of the past decade, with the MSCI World index gaining over 26% in euros. Whereas the decline in share prices in 2018 was due to a contraction of valuation multiples, the rise in 2019 can be explained by a fresh expansion of these multiples. In both cases, the primary cause was the US Federal Reserve's monetary policy. In 2018, the Fed raised its key interest rate four times, continuing the monetary tightening process it had begun in 2015. Last year, it made a U-turn, with three interest rate cuts.

The US central bank’s change of course was undoubtedly the defining factor on the financial markets in 2019. It was not justified by the economic situation in the United States: the economy is in its longest expansion cycle since the Second World War, the unemployment rate is at its lowest level in 50 years, and the inflation rate, while remaining moderate, has risen slightly. The fact that the Federal Reserve nevertheless loosened its monetary policy was due to the stock market decline in the fourth quarter of 2018. Prior to this change of course, investors were not too sure what tack the Fed would take under Powell. But this about-turn told them that, as was the case under Yellen, the Fed will continue to conduct its policy according to what happens on the financial markets.

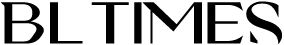

The European Central Bank quickly followed the Fed's lead by taking its absurd policy of negative rates a step further. Imagine an investor who had spent the last 10 years on another planet coming back today: seeing that the ECB’s key interest rate is negative, they would probably assume that the eurozone economy is in the midst of an economic depression, at least similar to that of the 1930s. But even though economic growth in the eurozone has certainly not been exceptional over the past decade, it has nevertheless been positive, and the unemployment rate has declined since 2013. Despite this reality, the monetary authorities have locked themselves into a bizarre logic. They continue to pursue extreme policies that are no longer justified by the economic fundamentals and seem to be largely influenced by the behavior of risk assets. The long-term effects of their policies could be very negative. By discouraging productive investment and propping up unviable companies that would otherwise fail, their measures are killing economic dynamism. On the other hand, they are encouraging the problem of moral hazard and excessive risk-taking.

Unemployment rate in the eurozone

Source: Macrobond

While the monetary policies conducted by the central banks are counter-productive from an economic point of view, in the short term they are reassuring for investors. Since the monetary authorities have made it clear that they are prepared to let inflation rise for a certain period before tightening their policy, we can theoretically rule out any of the leading central banks increasing their interest rates in 2020. At the very least, this should help support financial asset prices. It could even contribute to propelling them higher, unless the global economic situation deteriorates to a degree that would jeopardize corporate earnings. However, such a deterioration does not seem to be on the cards in the context of a lull in US-China trade tensions, expansive monetary policies, and the gradual abandonment of fiscal austerity.

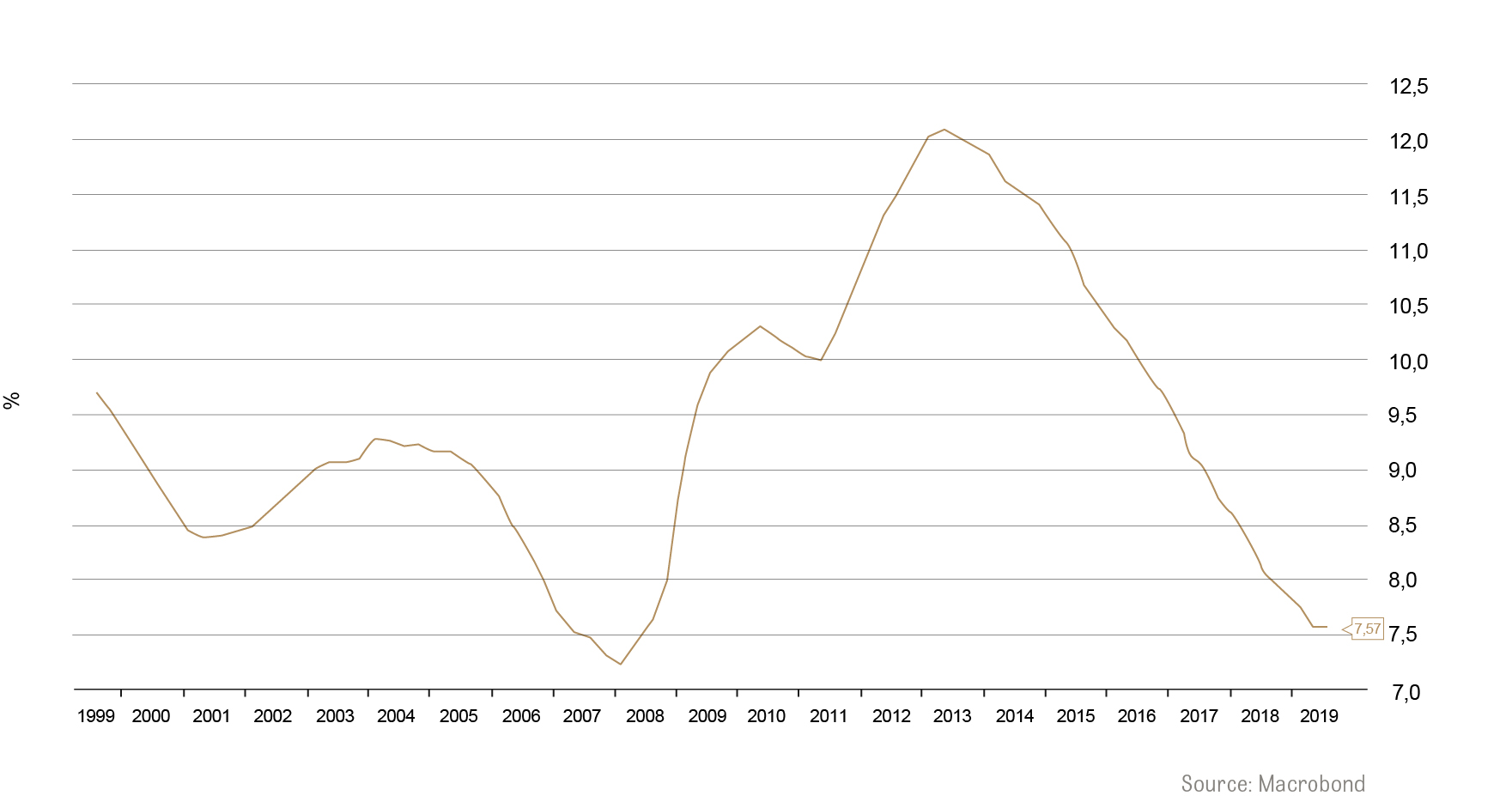

The main argument against equities is their high valuation. According to a number of ratios, the equity markets today are at valuation levels close to those of 1929 or 1999. However, today's higher valuation multiples should be seen in perspective. Three important factors could be considered to justify higher multiples than in the past. First, corporate profitability has increased. In the United States, the ratio of free cash flow to sales is now almost double its pre-financial crisis level. This can be explained on the one hand by the composition of the index (in particular, the technology sector’s higher weighting), and on the other hand by higher profit margins as a result of better cost control as well as more tangible elements such as lower tax rates and debt costs due to the decline in interest rates. This decline in interest rates is the second important factor justifying higher multiples. Equity valuation multiples are to some extent an inverse function of the risk-free rate. Most valuation models discount future flows (profits, cash flows, dividends, etc.). The lower the discount rate used, the higher the present value of these future flows, and therefore the multiple that an investor will be prepared to pay. Low rates also make equity market investments more attractive by reducing the appeal of money market and bond investments. Finally, a third factor justifying higher multiples is the supply/demand situation, as mergers and acquisitions, share buybacks and the relatively small number of new IPOs gradually reduce the supply of equities.

USA: Free cash flow in % of sales

Source: Standard & Poor’s, Russell, FactSet, Crédit Suisse

Returning to the level of interest rates, it would certainly be naive to think that low rates alone always justify higher multiples. In the past, low interest rates often reflected a deterioration in the economic situation (a pronounced economic slowdown, recession, etc.). Such a deterioration jeopardized corporate profits so that paying more for these companies was not justified. What is unusual in the current situation is that, as mentioned above, interest rates are historically low without such a deterioration having taken place. Although economic growth has certainly become weaker in industrialized countries, it has also become more stable. It could even be said that the environment has rarely been so favourable for equity valuation multiples. Equities are benefiting from very low interest rates without having to suffer from a particularly bad economic situation that would justify these low interest rates.

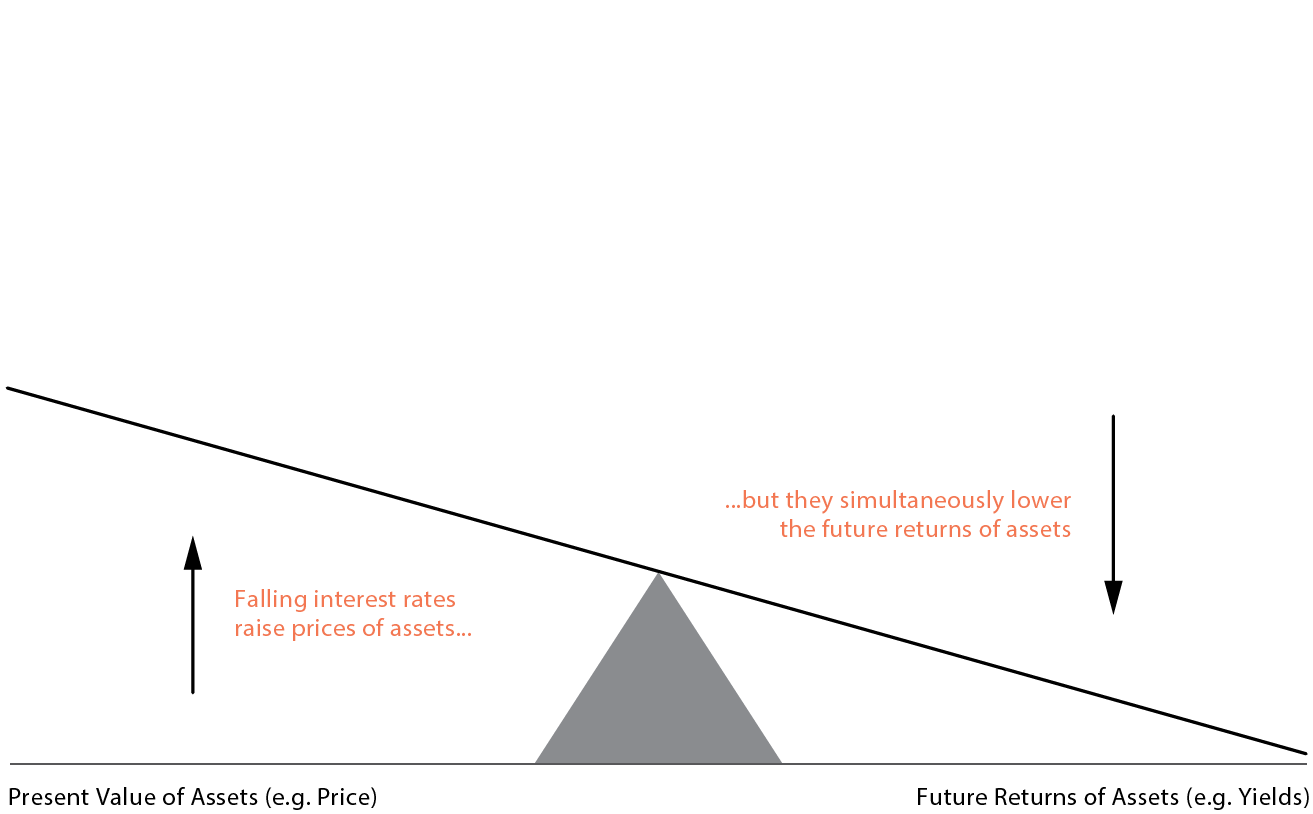

However, this should not lead us to conclude that multiples no longer have a role to play. An essential rule of any investment is that the price paid determines the return. But this link between the price paid and the return is determined over the long term, not the short term. The fact that shares are expensive today says nothing about their outlook for 2020. But it does say a lot about their potential return over this new decade. This potential, like that of bond investments, appears very low from current levels as the day will come when the elements justifying higher multiples today will invert; interest rates will rise and/or corporate profitability will decline. Against this headwind, equity market indices (and the passive management that replicates them) will find it difficult to generate positive returns. Thankfully, that day has not yet come, but we must remain very vigilant.

Current returns at the expense of future returns

Source: Bridgewater Associates

One argument we often hear is that the US market is very expensive whereas this is not the case for European or Asian markets. The differences in performance and valuation between the main equity indices are largely due to the composition of their respective indices. The weighting of ‘growth’ companies is much higher in the main US indices, headed by the technology sector, which accounts for almost 25% compared to less than 10% in Europe. In Europe, on the other hand, ‘value’ companies in sectors such as finance, telecoms and utilities have a higher weighting. To say that Europe will outperform the United States therefore boils down to saying that the value style will regain favour with investors at the expense of the growth style. While it is true that the discount on the former over the latter is historically high, the potential outperformance of the value style is likely to be short-lived unless there is a radical change in the macroeconomic environment.

Just because a new year has begun is not reason enough for a change in investment strategy. The factors behind the rise in equity prices in 2019, chief among them being the attitude of the central banks, are still very much in evidence. The fact that this rise took place despite an outflow from equity funds shows that investor scepticism towards equities remains high, which can be viewed as a positive. Investors should also be aware that, to some extent, staying out of equities means giving up on return, since the returns of other traditional asset classes (money market investments, government bonds, investment grade corporate bonds) have already become zero or even negative. Rather than dwelling too much on geographic or sector considerations, investors should also remember that ‘the stock market is a market of stocks’, and they should therefore focus on individual stock selection. They have the choice between high quality stocks that are more expensive but offer good earnings visibility, and lower quality stocks that appear significantly cheaper but whose earnings are substantially more erratic and more affected by economic and political uncertainties. Our management style will always favour the former.

In conclusion, it should be said that fears of a new financial crisis and a major market downturn caused by the underlying systemic problems certainly need to be taken seriously. But they seem premature. For a rational investor, it is never nice to buy at multiples that appear high in historical terms. At the same time, if investors want to protect or increase their long-term purchasing power, they need to act. Doing nothing is also a decision. Compared to investments in money markets and bonds, which in any case no longer yield anything and will be most at risk in the event of a new financial crisis, equities at least have the advantage of representing real assets.

One word about gold. After several years in a bear market, the yellow metal may be back on the up. It is negatively correlated to the level of real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) interest rates and there is no sign of these rising any time soon. It also represents a form of insurance against financial and geopolitical risks. The fact that central banks are again among the buyers shows that they do not seem too comfortable with their own policies (although we should note that it is mainly developing-country central banks that are buying).