Now might not be the best time to start a career in asset management

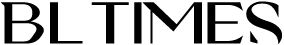

Being in the right place at the right time --- In every professional career, ‘chance’ plays a key role. The importance of being in the right place at the right time cannot be exaggerated. The asset management profession is a good illustration of this: someone starting to work in this profession in the mid-sixties will have spent a large part of their career seeing equity markets stand still. By the middle of 1982, the S&P 500 index stood at practically the same level as at the beginning of 1966. Since inflation was very high in the 1970s, an investment in that index would have generated a very pronounced loss of purchasing power. During the same period, interest rates rose sharply. From 4.5% in 1966, the United States 10-year interest rate climbed to over 13% at the beginning of the 1980s. It is hard for an asset manager to generate good absolute returns against such a headwind.

On the other hand, if the same asset manager had begun their professional career in 1982, the headwind would have been transformed to a very strong tailwind. Between mid-1982 and the start of 2000, the S&P 500 increased 15-fold, from 100 to over 1,500. Over the same period, the 10-year interest rate dropped from over 13% to below 5%. Difficult not to make money in such circumstances. Since 2000, the equity markets have been through challenging periods, but overall have continued to advance, witness the US market which now stands at double its early-2000 level. As for interest rates, they have quite simply practically disappeared and even become negative in many cases. But although the environment of the last 20 years has undeniably been more complicated than the previous two decades, it has nonetheless remained favourable for asset management.

Real S&P 500 index (adjusted for inflation)

Source: Minack Advisors

A changing environment

The financial markets’ rise in recent decades has been based on an unusual combination of factors, which primarily include the following:

- independence of the central banks,

- decline in inflation,

- globalisation of the world’s economy,

- demographic factors encouraging an increase in savings and hence demand for financial products,

- a relatively stable political order marked by US hegemony.

These trends have helped to drive down interest rates (helpful not only to bonds but also to equities due to lower financing costs for companies and an increase in valuation multiples) and boost corporate profit margins.

The concept of recency bias generally refers to the tendency among human beings of being more readily able to remember the most recent information they have come across. This bias often leads them to think that what has been true in the recent past will also be true in the future. Nearly four decades of rising financial markets have therefore left their mark on investors’ thinking and now heavily influence their expectations for future returns. But it is not without good reason that every financial product carries a warning that past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns. This is all the more relevant at a time when the above factors explaining high returns are in the course of changing:

- the central banks’ independence no longer seems to be set in stone. They are increasingly seen as having the financing of ever-higher public debt as their prime objective;

- although it is too soon to talk about a return of inflation, there is no denying that a number of the trends that contributed to disinflation are now starting to change. In any case, from current levels (1%-2%), any major change concerning inflation is not likely to please the financial markets, bringing with it either inflationary fears (with interest rate hikes) or deflationary fears (with payment defaults);

- the trend to decreasing customs tariffs and increasing global trade seems to be reversing;

- the baby-boomer generation is reaching retirement and is likely to start drawing on its savings. It needs a new generation to build savings to which it could sell its assets. Until now, this process of passing on to the next generation has never posed a problem, since each new generation has been richer than the last. For the first time since the Second World War, this is no longer the case;

- the hegemony of the United States is increasingly being called into question, creating a much more unstable political order.

Significantly lower returns

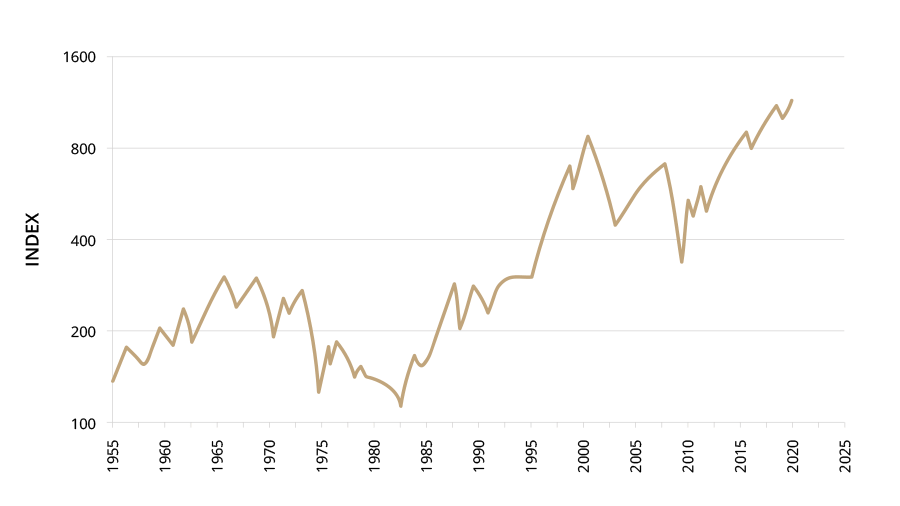

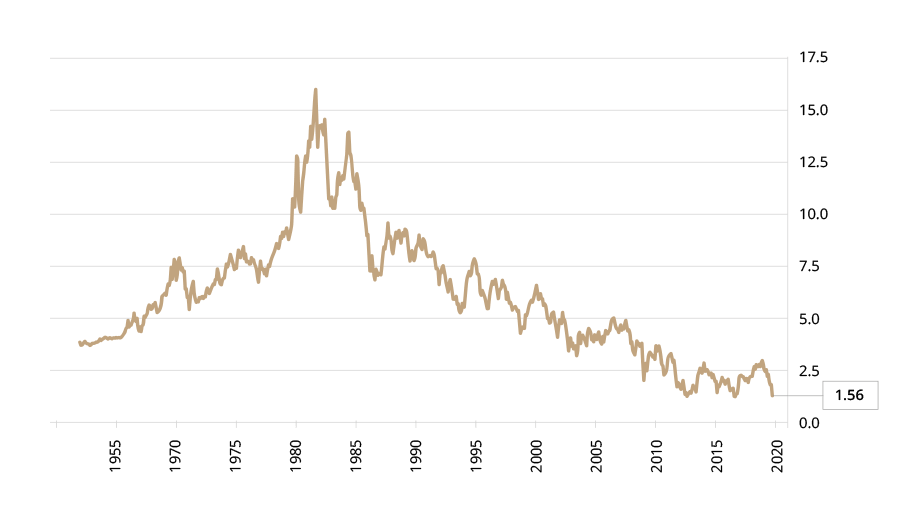

Added to this is the fact that the valuation of the financial markets is now very different from what it was at the beginning of the 1980s. At that time, Germany's 10-year government bond offered a yield of over 10%. That yield is now –0.7%. For bond markets, the future return is obviously in large part determined by the starting point. Realistically, the yield to be expected from a German 10-year government bond therefore amounts to a staggering ‑0.7%. For equity markets, the conclusion is not perhaps quite so direct but it is based on common sense: unlike in 1982, valuation multiples of equities are now high. Furthermore, these multiples are applied to profits that are themselves high, a consequence of several decades in which the share of wages in national income has steadily fallen. One could perhaps explain current multiples by the low level of interest rates but you cannot have it both ways, in other words pay a much higher price and expect to get the same return. Logically, it seems totally unrealistic to think that a ‘balanced’ portfolio, composed of 50% equities and 50% bonds, could, in the medium and long term, still generate the type of return that some people seem to expect (between 5% and 10% according to different studies).

US Generic Government 10 Year Yield

Source: Bloomberg

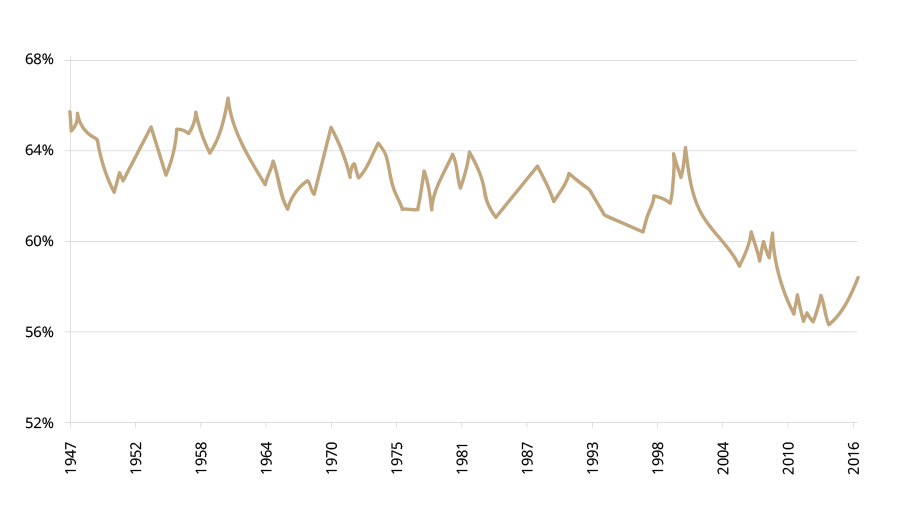

The futility of passive management

If we accept the idea that the returns offered by the leading asset classes in the coming years will be mediocre, the current trend towards passive management makes no sense. With very limited prospects for returns from the equity and bond indices, passive management will only, by definition, be able to produce meagre results (1). The only way to generate bigger returns will be through active management and trying to produce idiosyncratic returns. Yet very few asset managers are prepared to do this. Active management often means going off the beaten track and not buying what is popular (but often expensive) and instead investing in assets that have been disregarded and are unpopular (but often good value). The problem with this approach is that while it makes a lot of sense over the long term (provided the asset manager does not make too many mistakes), it can have disappointing results in the short term, given that what is popular can continue to rise and what is disregarded will continue to suffer. Without very loyal clients, an asset manager's career may well come to an end before the long-term results validate his or her decisions. The famous economist, Keynes, used to say that worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally. As a result, many asset managers confine themselves to the intellectually rather unsatisfying task of slavishly following the indices. For equities, this means buying shares that have risen considerably (the rise in their share price having increased their market capitalisation and hence their weighting in the index), while for bonds, it means buying the most indebted issuers (which also have the highest weighting in the index). Even if they want to be more active in their management, sometimes absurd regulatory constraints limit their room for manoeuvre. By way of example, it is demoralising to see that such constraints force so-called ‘prudent’ clients to hold the majority of their assets in bonds, given that these investments either offer a negative yield or are issued by debtors of increasingly doubtful quality.

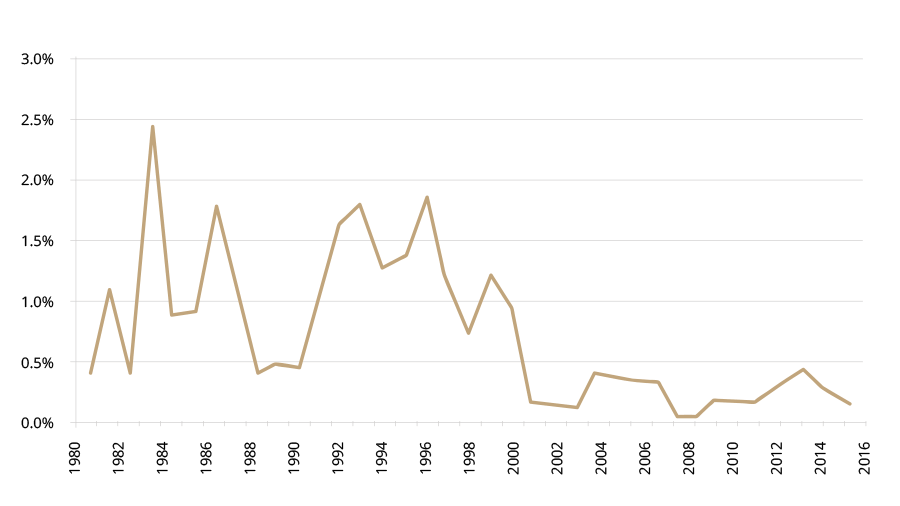

Labor's share of nonfarm business sector output

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Another factor that makes the work of an asset manager difficult today is that there is no longer any certainty that equity markets will function properly. On the supply side, the number of listed companies is declining. This is due as much to the wave of mergers and acquisitions as to the small number of new market introductions. The time when the equity market was a source of financing for companies, especially growth companies, seems to have passed. On the demand side, we see a growing number of investors who pay little heed to valuation, such as tracker funds, central banks and companies buying back their own shares. All this has consequences on the process of price-setting, liquidity, democratisation of access to growth companies and, more profoundly, the utility of fundamental analysis where the objective is to find undervalued assets whose undervaluation could reasonably be expected to correct sooner or later.

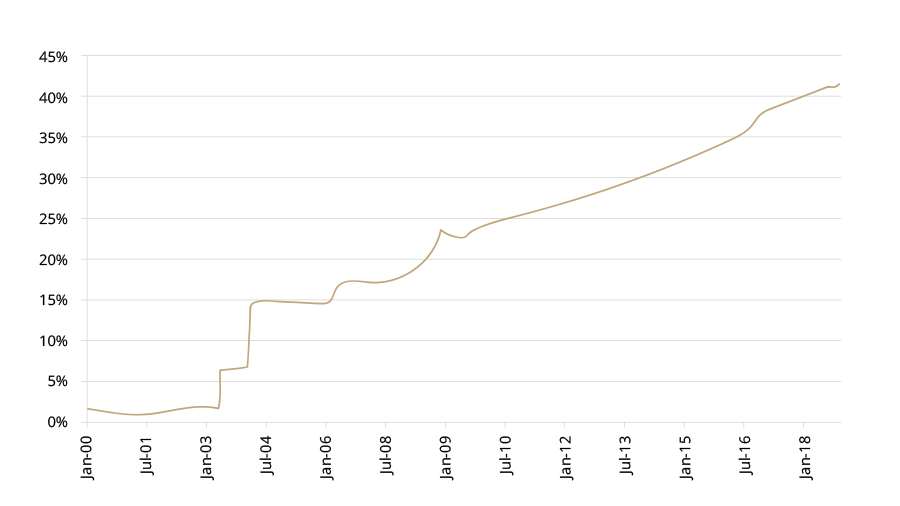

Passive share of total global equity fund AUM

Source: EPFR Global and Bernstein analysis

And yet

The need for high-quality asset management has never been so great. Despite some 35 years of rising financial markets, pension plans for both governments and companies are generally dramatically under-capitalised. And these plans still use expectations for returns that are totally unrealistic. The same is true for endowment funds and even for private investors. Ultimately, all these agents will either have to increase their contributions or reduce their expenditures in one way or another. The pension shortfall also explains why the idea that very low interest rates will boost growth, particularly by stimulating consumption, is doomed to fail. The average person is not stupid and knows very well that in the absence of a return on fixed-interest investments, they will have to save more. As a result, savings rates increase as interest rates fall.

Nevertheless, high-quality asset management requires a contrasting approach to that currently in evidence. The obsession with benchmarks and short-termism will have to change. Obviously, comparing asset managers to an index is a simple way of judging them. But it is also a simplistic approach insofar as the index used often bears no relation to the investor's real needs. For investors faced with prescribed commitments, the first objective will be to generate the necessary revenues to meet these commitments. But even for investors without specific commitments, the objective is not generally to beat such and such an index but to generate the necessary revenues to meet commitments within the real economy, which are impacted by the increase in the cost of living. These needs often relate to education, healthcare or retirement. Beating an index like the S&P 500 or the Stoxx 600 is all well and good when the index is rising since in this case good relative performance equates to good absolute performance (and at the end of the day, absolute performance is what really should concern investors: you cannot eat relative performance). In an environment when these indices are likely to fall rather more often than in the past, the situation will be different: delivering –10% when the market is turning in –15% will not help protect investors’ purchasing power. Rather than judge an asset manager on their relative performance, a different approach could be to target specific results.

Number of Initial Public Offerings as a percentage of listed firms

Source: Updated Statistics, Jay Ritter, Cordell Professor of Finance, University of Florida (December 31, 2018) and Bernstein analysis

Confidence being the missing link

A crucial element that is often lacking in today's client-asset manager relationship (and increasingly in society as a whole) is confidence. Numerous studies show that many clients have much too short an investment horizon when they could have a much longer one, and that regularly changing asset manager or individual stocks destroys value. But it would be unrealistic to think that such investors are prepared to extend their investment horizon if they don’t have (much) confidence in their asset manager. (Paradoxically, though, they are prepared to accept much longer investment horizons, much lower liquidity and much higher fees in alternative management even though this a much more opaque management style.) It is true that many asset managers have not covered themselves in glory in the past and that some high-profile scandals have harmed the profession, obscuring the fact that the majority of asset managers are trying to work in their clients’ interest. How can the situation be improved? A fee structure more closely aligning the interests of the two parties could be sensible. However, this might not be very easy to institute (and some would say it exists already since asset managers usually get a fixed fee based on clients’ assets, providing an incentive to increase them). One possibility would be to replace fixed management fees by performance-linked fees but in this case, there would have to be agreement on how to measure performance.

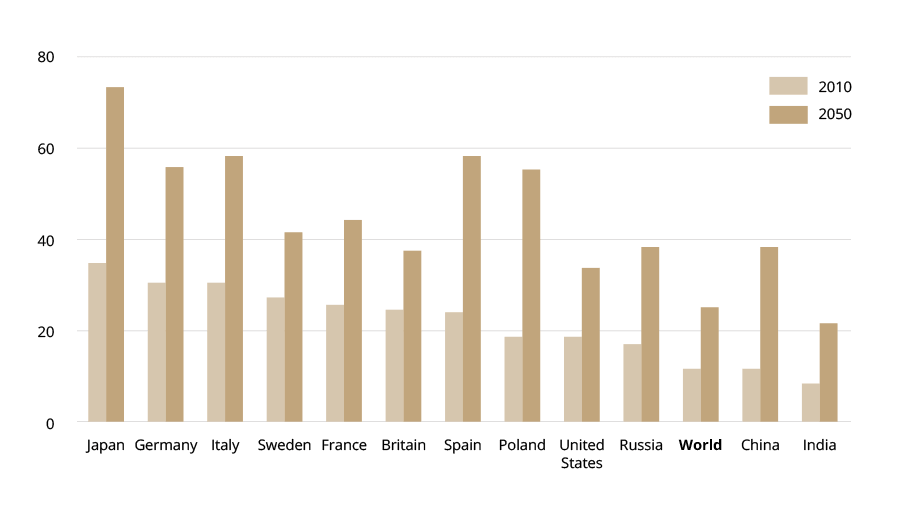

Old age dependency ratios (number of people aged 65 and over as % of labour force (aged 15 - 64)

Source: European Commission

An objective going beyond simply maximising the return

Another phenomenon in the process of changing what is expected from high-quality management concerns socially responsible investment. For a long time, the objective of asset management has been to maximise the return generated or to beat a benchmark index without regard for the type of assets or companies selected. In some countries, the concept of shareholder value was thus pushed to the extreme, disregarding the fact that a company has other stakeholders like employees, customers and suppliers. Increasingly, other criteria are now coming into play and asset managers are expected to contribute to the objectives to which society as a whole aspires, whether in terms of the environment, treatment of employees or other factors. And if the profession can play a role in achieving these objectives, the return it will generate may be less tangible, but nonetheless real. And its reputation will be enhanced. At present, the quality of research regarding everything affecting environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria is still poor and the providers specialising in this type of research frequently reach very different conclusions about the companies they study. Nevertheless, the trend to incorporate such criteria in investment decisions seems irreversible and asset management must contribute to advancing the cause.

The fact is that the golden age of asset management has turned full circle. And to the extent that the profession has seen numerous activities appear in recent years that make zero contribution to the well-being of society as a whole (such as developing algorithms for hedge funds), this can even be seen as a good thing. At the same time, the issues involved in building one's savings to prepare for the future are still just as vital. This is why the need for high-quality asset management – and hence high-quality asset managers – has rarely been so important.

A young person starting out in this profession today may not necessarily be able to say in twenty years’ time that they were in the right place at the right time. The best advice they can be given is in the title of two of the renowned memos regularly written by Howard Marks, President and Co-Founder of Oaktree Capital Management: Dare to be great.

______________

(1) Obviously asset management is never entirely passive. You can invest passively on the US stock market by buying tracker funds, but the decision to invest in that market is still an active one.