Sector rotations and relative performance of our funds

Within the equity markets, several rotations have been observed in recent months: investors have shifted from growth to value, high quality to low quality and defensive to cyclical. Some will date the beginning of these rotations to November of last year when the first Covid 19 vaccines were announced, others will say that they started as early as July 2020.

In any case, these rotations are not favorable for the relative performance of our funds, which favor (and will always favor!) quality and do not (or rarely) invest in most of the sectors generally associated with the 'value' style (banks, commodity producers, car manufacturers, airlines, ...). The question arises whether these rotations, which are detrimental to the performance of our funds, are likely to continue. To do so, it seems appropriate to:

- Review the economic conditions that led to these rotations (and whether these conditions will last).

- Put these rotations in a historical context in terms of amplitude and duration.

Before doing this, it is useful to go back to the reason that led us to opt for an investment methodology that favors certain sectors (consumer cyclicals and staples, industrials, technology, health care, etc.) and tends to neglect others. The reason for this is that in some sectors it is difficult to find the kind of company we are looking for and in which we would like to take a long-term stake. We look for companies that are able to generate a high return on the capital they employ (ROCE). Every business needs capital to operate and that capital has a cost. If a company uses debt, this cost is usually known, as it is the interest the company has to pay on its debt (although this cost can change if the company has to refinance its debt). If the company is financed by equity capital, this cost can only be estimated, but it can be assumed that the cost of equity is higher than the cost of debt (since the shareholder who takes an equity stake in the company takes on much more risk than the creditor who simply lends money and is repaid first). In our valuation models, we generally work with a cost of equity of between 8% and 10%. Only companies that are able, on a recurring basis, to generate a return on capital employed that is significantly higher than the cost of that capital are able to create value for their shareholders over time. In some sectors, however, the return on capital employed is structurally low. These are typically sectors characterized by a high number of players (leading to a lot of competition), high capital intensity (meaning that a large part of the cash flow generated must be reinvested in the production apparatus and cannot be distributed, in one form or another, to the company’s shareholders), high sensitivity to economic conditions and, in general, a lack of sustainable competitive advantages. It is possible to make money by investing in companies in these sectors, but only if you have very good timing: buy at the right time and sell at the right time. If, on the other hand, the timing turns out to be bad, the risk of losing capital is important. Timing also means by definition that the investor has a short-term investment horizon. Insofar as our entire management philosophy is based on the conviction that in order to protect and grow our clients' capital, it is important to avoid major losses, and that we consider the purchase of a share as a long-term participation, it is obvious that we are not very interested in these kinds of companies.

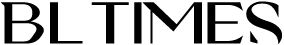

The following calculation illustrates this. It assumes that an investor has a choice between buying a high-quality company (20% return on capital employed) at 20 times earnings (company A) or buying a lower-quality company (8% return on capital employed) at 10 times earnings (company B). 10 years later, both companies are trading at 15 times earnings.

Despite the decline in the multiple of the high-quality company and the increase in the multiple of the lower-quality company, the performance of the former will be well above that of the latter. Also, I have been very generous with the lower quality company by assuming that it manages to generate a return on capital of 8% on average (most companies in sectors associated with the value style generate a much lower average return on capital) and by assuming that its multiple increases by 50%.

10-year return

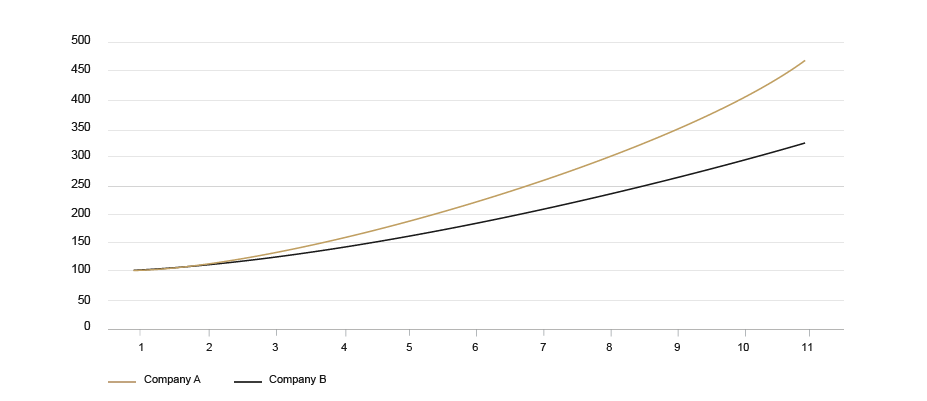

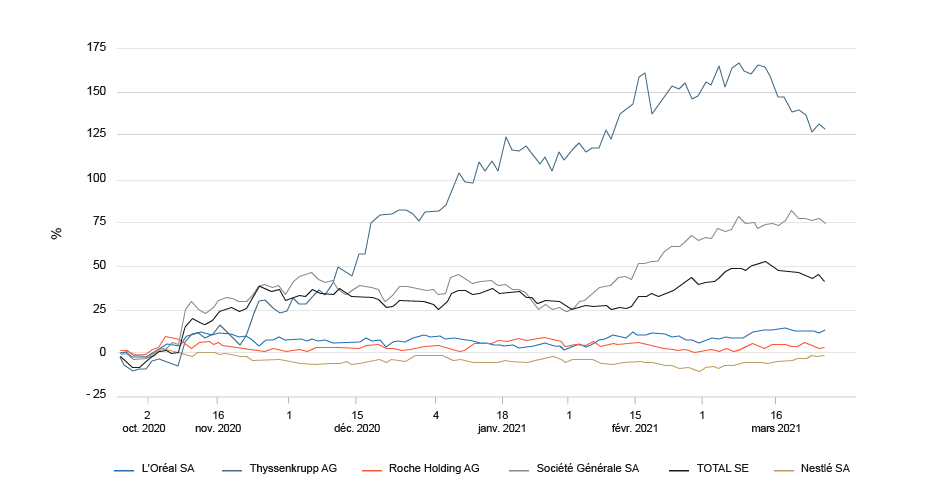

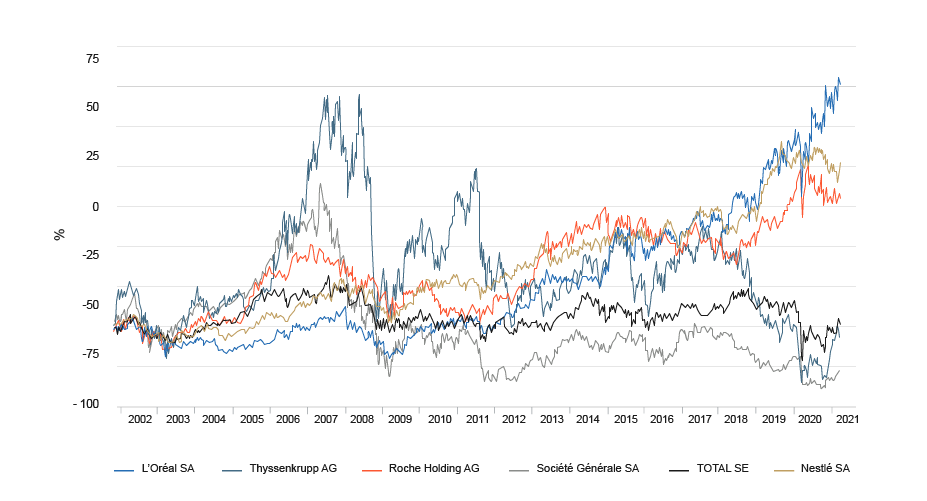

Another way to illustrate the same idea is to look at the performance (excluding dividends) of 6 stocks: Total, Société Générale, Thyssen, Roche, L'Oréal, Nestlé. The first 3 tend to be associated with the value style, the last 3 with the growth style. The charts below show the performance of these 6 stocks since November 2020, over 3 years and over 20 years. A picture tells a thousand words. (Note that these returns do not include dividends. If dividends were included, Total's performance would be much more favorable, while remaining well below that of L'Oréal, Nestlé and Roche).

Since November 2020

Source: Macrobond

Over 3 years

Source: Macrobond

Over 20 years

Source: Macrobond

That being said, what should we think of the rotations currently underway? First of all, it should be noted that they seem perfectly logical given the current economic conditions. The markets are currently anticipating a strong acceleration of the global economy and a rise in inflation but no tightening of monetary policy by the major central banks, starting with the Federal Reserve in the United States. The U.S. could thus experience its highest growth rate in nearly 40 years. Companies typically associated with the value style benefit from this environment as their earnings are often cyclical. Much of the value that investors are willing to place on these companies is thus determined by their short-term results, given the lack of visibility on their longer-term results. This is not the case for quality companies, which offer much more visibility on their long-term results. As a result, they are often considered high-duration assets. In phases of rising long-term interest rates, they therefore tend to (temporarily) lose favor with investors, as is currently the case (in the US, the 10-year bond yield has risen from 0.5% to 1.6% since August 2020). At present, there is no sign that the economic conditions for the current rotations are about to change.

If the underperformance of quality assets is therefore likely to continue for some time, where are we in terms of magnitude and duration? The last major phases of value outperformance occurred in 2002/2003 and 2009/2010 (a shorter phase occurred in 2016). These phases lasted between 14 and 18 months. If we put the start of the current phase somewhere between July and November of last year, we would only be 5-9 months into it and we should not expect the situation to improve (in terms of the relative performance of our funds) until the end of the year. In terms of magnitude, the situation looks a little more favorable. Based on past experience, one could say that about three quarters of the outperformance of the value style has already been realized. As far as the rotation from defensive to cyclical stocks and from high quality to lower quality stocks is concerned, it seems to be even more advanced and should therefore penalize us less from now on.

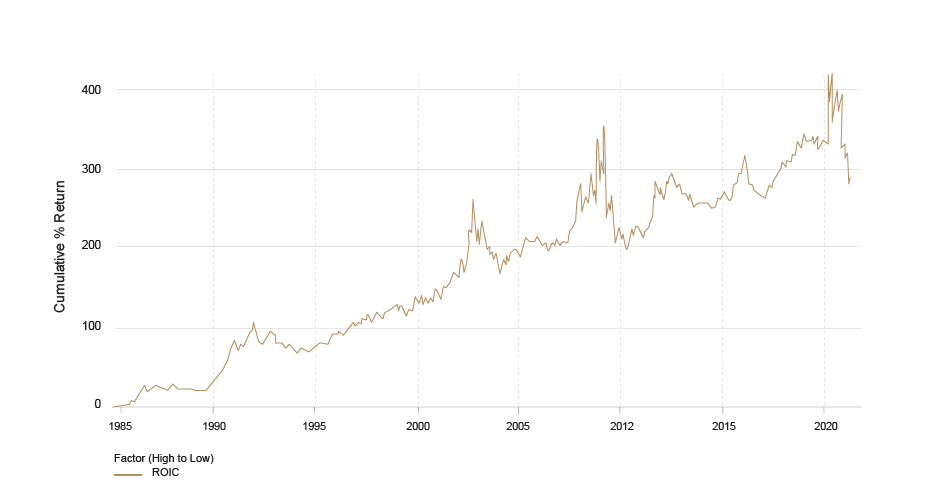

The two graphs below illustrate this by showing the relative performance of companies in the top quintile in terms of return on capital employed relative to those in the bottom quintile (universe: S&P 500) and the relative performance of the consumer staples sector (universe: MSCI world).

Relative performance 1st quintile / 5th quintile

Source: CornerstoneMacro

A 12-year relative low point for the consumer staples sector

Source: Macrobond

In conclusion, unless there are developments that call into question investors' current optimism about the economic outlook, there is a good chance that the stock market environment will not change any time soon and will remain rather unfavorable to our management style. Forewarned is forearmed. But this does not change the relevance of this style over the long term. And to quote Terry Smith, founder and CEO of Fundsmith, "And if you are not a long-term investor, I wonder what you are doing in the stock market at all. And so will you one day."