What investors can learn from foresters and family-owned companies (Part II)

In the first part of this article, we pointed out that the term “sustainability” had come from forestry, and that family-owned companies had performed significantly better over the study’s 17-year observation period. We also reported that the number of publicly traded family-owned companies in Europe is quite geographically heterogenous and that both family-owned companies and the comparison group had shown on a solid liquidity position over the period under review. In this second part, we will explore the issues of equity ratio and return on equity.

Family-owned companies with high equity ratios

Generally speaking, the equity ratio is a measure of a company’s financial stability. The equity ratio is a company’s percentage of equity capital to total capital. The higher the equity ratio, the higher its credit rating tends to be. This is based on the argument that a company with a high equity ratio is less dependent on debt capital and is therefore in a position to self-finance to a greater extent. This has an impact on the company’s costs (lower debt = lower interest rates and debt burden = greater financial wherewithal) and also speeds up its investment process, as the company controls the process alone and doesn’t have to go through the (sometimes time-consuming) process of raising debt capital.

However, the companies in our study are not charitable institutions that have cost-free equity capital at their disposal. Equity investors expect to share in the company’s profits. For very good reasons, we have assumed that the cost of equity capital is higher than the cost of borrowing. Equity investors assume a greater risk than debt investors, as they are subordinate to debt investors in the event of insolvency. Their (total) risk of loss is therefore far higher.

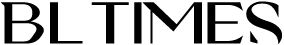

Equity ratio

A mere glance at the above chart shows that family-owned companies had far higher equity ratios during the period under review. Moreover, the equity ratio at family-owned companies did not fall appreciably during and after the financial crisis. A closer look at the study’s findings reveals that between nine and 14 family-owned companies had an equity ratio of more than 90 percent from 2002 until 2008, vs. just three to seven companies in the control group.

This indicator also suggests that family-run companies apparently place greater importance on independence, security and stability.

But what about return on equity? As we alluded to previously, the company’s owners expect a market-like return on their capital.

Surprising findings regarding return on equity

Return on equity is the ratio of profits to equity capital. The higher the ratio, the greater the return on equity. However, return on equity alone is not very meaningful as an indicator. One variable in calculating return on equity – as we discussed above – is the equity ratio. The higher the equity ratio, the harder it is to achieve a high return on equity.

However, it is always worth taking a close look at what’s going on behind the scenes at each individual company. Incidentally, this is a basic reason we are big proponents of active investment management. Only a comprehensive analysis of a company reduces the risk of error and teaches us about its current and future competitiveness.

But back to the subject at hand: generally speaking, a high return on equity goes hand-in-hand with a positive assessment of the company. However, the reverse (low return on equity = negative assessment of the company) is not necessarily true.

On the one hand, return on equity should always be seen in sector terms. There are capital-intensive and/or cyclical sectors whose returns on equity can drop precipitously. In these cases, only multi-year sector comparisons can produce meaningful data.

On the other hand, companies can also “buy” high returns on equity by raising debt capital and, thus lowering their equity ratios.

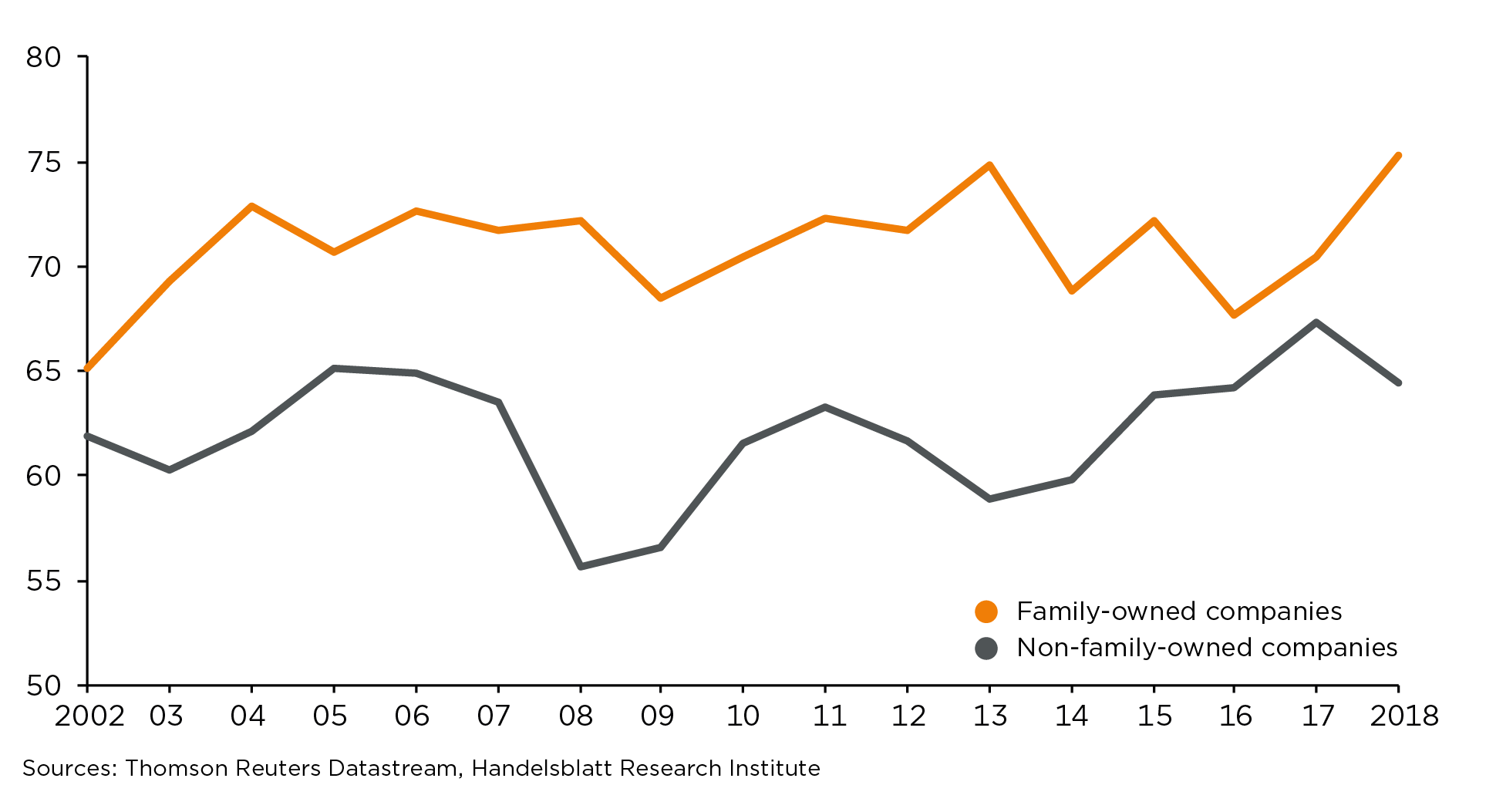

A short observation period therefore makes little sense. Only the entire observation period provides meaningful conclusions companies’ return on equity. Family-owned companies’ return on equity was found to be relatively stable over the entire observation period, with no significant outliers.

In contrast, the control group was significantly more volatile, with a peak ratio of almost 20 percent in 2007 that fell to 6.3 percent within two years, whereas family-owned companies remained well into double-digit percentages.

Return on equity

This volatility during the observation period was due to the accumulation of year-on-year net results. At family-run companies these fell by 19 percent in 2008 and by 34 percent in 2009, the two years of the financial crisis. The year-on-year declines were far more drastic in the control group, at 29 percent in 2008 and a further 48 percent in 2009.

When including equity ratios during the observation period, the findings on performances are surprising. Even with a far higher equity ratio, family-owned companies achieved a similar but more stable return on equity.

The study accordingly suggests that family-owned companies take a longer-term view and enjoy more solid financing. They are therefore more robust during recessions and provide higher returns to their investors.

All of this leads us back to the question we asked at the outset – what can investors learn from foresters and family-owned companies. Lots, it turns out. As Georg Ludwig Hartig wrote in 1804 in his instructions, sustainable forestry is only possible if trees that were cut are at least balanced out by reforestation, so that future generations can benefit from them – in both the economic and environmental sense.

Cross-generational thinking is also the rule at family-owned companies. This is facilitated by a solid financial situation and a sharing of the company’s success with its owners (i.e., the shareholders) that is commensurate with the risk they have assumed. In addition, family-owned companies are often highly specialised and have close ties to their clients and employees. And experience has shown that family-owned companies can often react very flexibly in meeting their clients’ needs.

Translating all this into an investor’s point of view yields the following conclusions:

First, of all, the concept of “investor” should be clarified. We make a clear distinction between “investor” and “money manager” or “capital market participant” or similar terms. An investor, by definition, has an interest in the long-term success of his investments, similar to foresters and family-owned companies.

Investors thus often develop a long-term strategy that, while being fine-tuned and adjusted to economic circumstances over time, remains constant at its core. They aren’t trying to “beat” the market over the short term. In any case, it’s an illusion to believe that one can consistently beat the market through short-term trading. Just the steady flow of daily news and events that everyone is confronted with makes this impossible.

However, concentrating on what is essential – investing in companies that you understand, a strategy that is based on long-term thinking and is focused on high-quality investments – should yield promising results.

Those who see things differently should perhaps have a talk with family-owned companies… and foresters.